Judo Canada

1924 -2024

Dear Judo Canada members

2024 is the 100th anniversary of organized Judo in Canada, which began with the establishment of Tai Iku Dojo by Shigetaka ‘Steve’ Sasaki in Vancouver in 1924.

Judo Canada encourages all organizations, clubs, and individual judoka to support the 100 campaign that we will celebrate.

1924

Foundation of the 1st permanent Dojo Tai Iku

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

“As the “father of Canadian judo,” Steven Shigetaka Sasaki deserves special mention in any historical work devoted to the sport…”

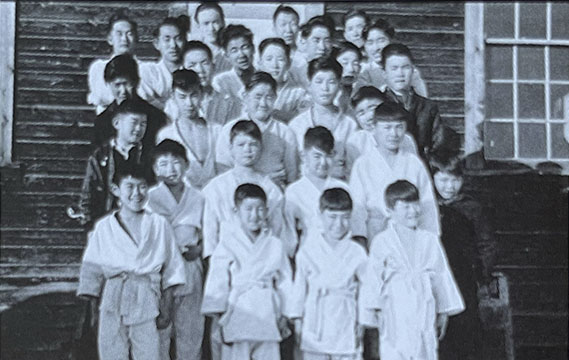

“Shigetaka Sasaki arrived in Canada in 1922 with the rank of 2nd dan. In Japan, he taught judo at Yonago High School. Although he recognizes a certain practice of discipline in British Columbia, he judges that teaching is done haphazardly. So he brought together the Japanese community in Vancouver to gauge interest. Over the course of a year, Sasaki plans, organizes other meetings, forms a stakeholder group and solicits sponsors. In 1924, he opened his first dojo.

As with any business started from scratch, things don’t go smoothly. First you need to find a training room. At the beginning, the lessons were given in the high-ceilinged living room of one of the sponsors, Mr. Kanzo Ui. It is not known whether the latter follows the lessons himself. The house is located at 500 Alexander Street in Vancouver. The tatami mat was purchased with money raised by another sponsor, Mr. Ichiji Sasaki, owner of a sushi restaurant. The Vancouver Tai Iku dojo was born.”

The expansion

Mr. Ui’s living room does not house the Tai Iku dojo for long. In a few months, so many Vancouverites of Japanese origin registered that we had to find new premises. What is done, Powell Street.

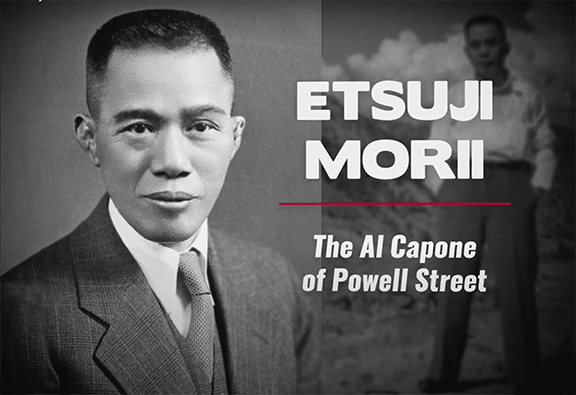

It costs $0.30 for adult students, $0.10 for boys and $0.05 for girls to attend the dojo. We do not know today whether this rate is then charged per session, per week or month. One thing is certain, income is so minimal that Sasaki has to dip into his personal money to pay running costs, rent, electricity and water. Far from being profitable, the company would probably founder without the sponsors who end up assuming part of the financial burden. Among them is the club’s main benefactor, Etsuji Morii, businessman and judoka.

The same “no-profit” scenario will repeat itself throughout this period of expansion. The roots and development of judo are accomplished for pleasure. Not only do teachers or masters, one after another, spread “the good news” voluntarily, but they even have to pay out of their own pockets for this privilege, as demonstrated by the adventure of Shigetaka Sasaki in establishing the first permanent dojo. No doubt they are then carried by the spirit of seiryoku zenyo and jita kyoei – maximum efficiency and mutual prosperity.

In 1927, another club was founded in Steveston, British Columbia. The instigators of the project, Tomoaki Doi, director of the youth program and judo teacher, and Mr. Takeshi Yamamoto seek Sasaki’s help. Despite the busy schedule of running his business and leading a fledgling organization, Sasaki travels to Steveston twice a week. The Steveston dojo therefore becomes a subsidiary of the Tai Iku dojo in Vancouver. Other branches opened in Kitsilano, Fairview, Haney, Mission, Woodfibre and, on Vancouver Island, Chemainus, Victoria and Duncan. Sasaki tirelessly gets personally involved in teaching or persuades others to get involved. Whonnock and Hammond also have their dojo.

Among the senseis of the time were Atsumu Kamino (Kitsilano), Tomoaki Doi (Steveston), Masatoshi Umetsu (Fairview), Eiichi Hashizume and Yoshitaka Mori (Mission), Tomutsu Mitani and Kasuta Ryoji (Haney), Frank Mukai (Tai Uku ), Shigeo Nakamura (Duncan), Mitsuyuki Sakata and Genishiro Nakahara (Chemainus), Kametaro Akiyama (Victoria) and Satoru Tamoto (Woodfiber). For their part, all judokas are of Japanese origin, either isseis (born in Japan) or niseis (born in Canada to Japanese immigrants). But that will change from 1932.”

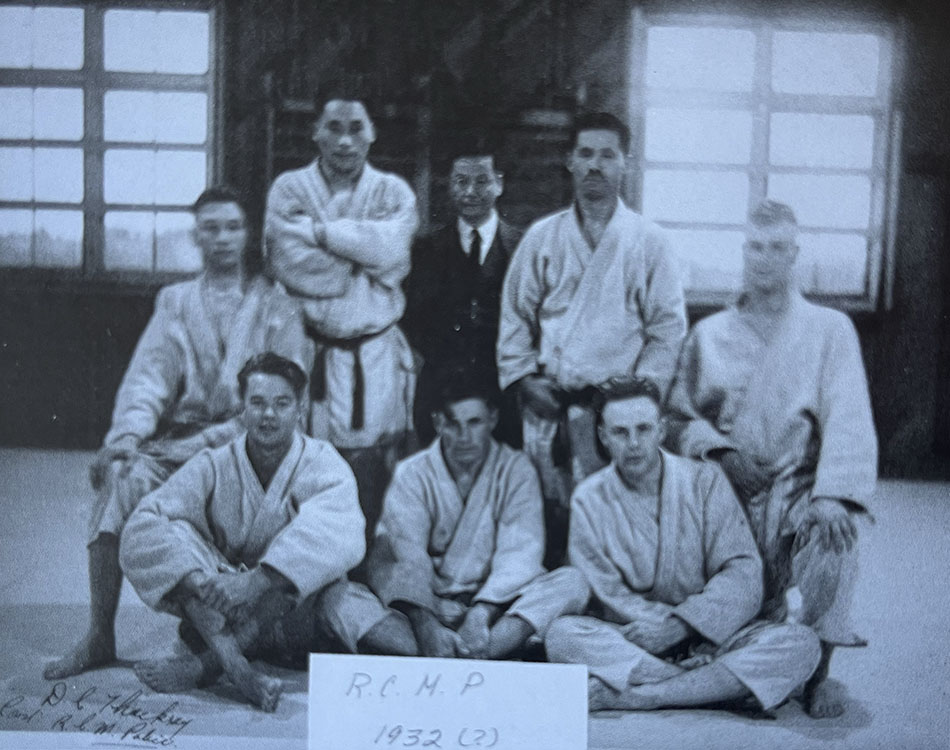

“The RCMP

The RCMP approached Shigetaka Sasaki in 1932, intending to introduce its officers to judo. Aware of the breakthrough his discipline could experience in the country thanks to this opportunity, Sasaki decides to take charge of officer training himself. A close relationship was then established between the sensei and the RCMP which would serve Sasaki on many occasions.

That year, in February, a judo tournament was held in Vancouver, attended by the director of the local RCMP detachment. The man was so impressed by the demonstration that he asked Ottawa for permission to replace boxing and wrestling with judo in the training of officers. With Ottawa’s blessing, we speak to Sasaki. This is how 11 officers began training twice a week at the detachment gymnasium, 33 Heather Street. This is probably the first time that judo has been taught to white people on Canadian soil. The same year, Sasaki went to Japan to study under Kyuzo Mifune, 7th dan in Kodokan and chief instructor. He is promoted to 3rd dan. »

For more history :

BC Sports Hall Of Fame

Judo British Columbia

Centre Nikkei Place – Japanese Canadian National Museum Newsletter ISSN#1203-9017 Summer 2002, Vol. 7, No. 2 – A History of the Steveston Judo Club by Jim Kojima:

The Steva Theatre mentioned in the newsletter A History of the Steveston Judo Club

Steveston Dojo now

Founded in 1944, the Vernon club is the oldest still in operation in Canada. Its founder, Yoshitaka Mori, was a former resident of Mission, (B.C.)

Vernon Judo Club Now

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1932

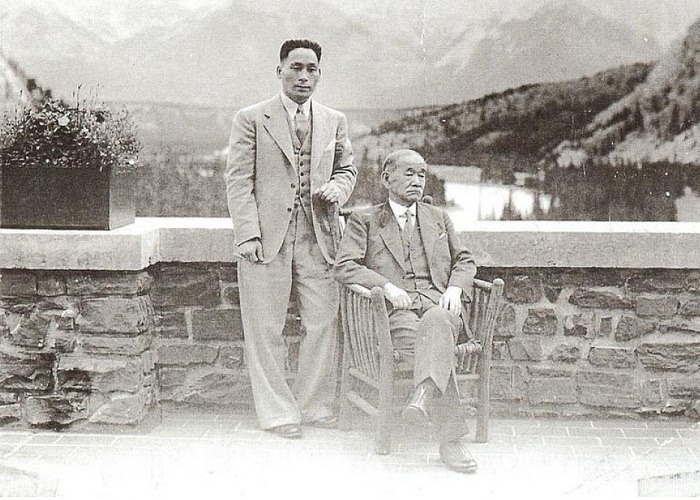

Master Jigoro Kano First visit to Canada

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

At the same time, the founder of Judo, Dr. Jigoro Kano, on his return from the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, visited the Tai Iku Dojo in Vancouver. He renamed the dojo Kidokan – “House of Intrinsic Energy”. All other dojos in B.C. became branches of the Kidokan. This was a great honour for the young club. Professor Kano added to the special occasion by granting honorary black belt status to the three members of the Vancouver Club: Eichi Kagetsu, Gentaro Isobe and Toshiaki Sumi. These were unique titles created by the Master because the three recipients had never competed in a tournement. They had given financially, mentally, spiritually and physically to the sport, and Professor Kano sought to recognize their contributions by this special status.

For more history :

Eikichi Kagetsu

Jigoro Kano visited Vancouver again in 1937 :

Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Center

Prince Chichibu’s visit to Canada 2

Shigetaka (Steve) Sasaki Family Fond

The Ocean liner seen in the video is Heian Maru and is the sister of the Ocean liner Hikawa Maru place of Master Jigoro Kano’s death

Hikawa Maru

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1956

Establishment of the Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association (CKBBA)

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

«In February 1942, the Federal Cabinet passed an act which launched a shameful period in Canadian history. Responding to paranoia, the government ordered the expulsion of some 22,000 Canadians of Japanese origin from their homes if they resided within 100 miles of the Pacific Coast. Seventy-five percent (75%) of the affected individuals were either born in Canada or naturalized. This order was not rescinded until March 31,1949, even though the war ended in August 1945.»

« Many are the stories of the beginnings of small clubs started selflessly by men who had learned their judo in B.C., nurtured it through wartime, and then established nuclei across the country like seeds blown from a plant. Each seed begot a mature tree which, in turn, produced more seeds and more trees.»

« Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association

When the judokas from B.C. began to roll into Toronto after the war, it was natural for them to look up old judo friends scattered as a result of the expulsion, and the easiest way to find those in the Toronto area was to visit Atsumu Kamino’s dojo in the basement of The Church of All Nations on the corner of Spadina and Queen. The dojo established in 1946, was named the Kidokwan Judo Institute after the original Vancouver Kidokan Club, which had been the headquarters dojo in prewar B.C. With so many judokas in one city, it was natural for Kamino, 3rd Dan at the time, and third-highest rank in Canada (to that of S. Sasaki, who was now residing in Ashcroft, B.C., and E. Mori), to organize these black belts and form an executive board to look after the business of judo, which included the granting of grades. Thus, the “ Canada Judo Yudanshakai “, the forerunner to the Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association, was formally established. But now occurs a strange step in the judo history.

The Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association, CKBBA, or what was later to become Judo Canada, was incorporated in 1956, but it was not officially recognized by the International Judo Federation until 1958. There was already another judo organization in Canada, founded by Bernard Gauthier. Gauthier was a self-taught expert with no connection with the Kodokan. His judo followed the Mikinosuke Kawaishi system, which he studied through books, and on weekends he travelled to Montreal to learn from Frenchman Marc Scala. Gauthier fought in the 1st Judo World Championships in Tokyo in 1956 representing Canada.

Earlier, in 1949, Gauthier, ever ambitious, applied to the Canadian Government for a charter to establish the Canadian Judo Federation (CJF), and in 1952 his fledgling organization set out to organize a number of Canadian Championships under the auspices of the CFJ. The first one was in 1952, and Gauthier got the Japanese embassy in Ottawa to sponsor it by donating the championship trophy. To add lustre, he invited the International President Risei Kano, son of Founder kano, and All Japan Champion Daigo to be present.

The second CJF-sponsored national tournament was held in Toronto in cooperation with the Kidokwan. Marc Scala, who had moved from Paris to Montreal in 1950 and was a disciple of Mikinosuke Kawaishi, took home the coveted championship plaque courtesy of the Japanese embassy. Frank Hatashita’s Toronto club won the team title, something they would do many times.

But for Atsumu Kamino, the symbolism of watching the plaque being taken away from those who had done so much for Canadian Judo, nursing it through the hard times, was too much to overlook. And when Gauthier represented Canada at the First World Championships in Tokyo, Japan, it hit too close to home.

The Toronto judokas, under the quiet leadership of Atsumu Kamino, then set about to correct the situation. They legally incorporated the existing Canada Judo Yudanshakai in order to give legitimacy to their own national organization. Letters patent for the newly formed organization were issued October 25, 1956.

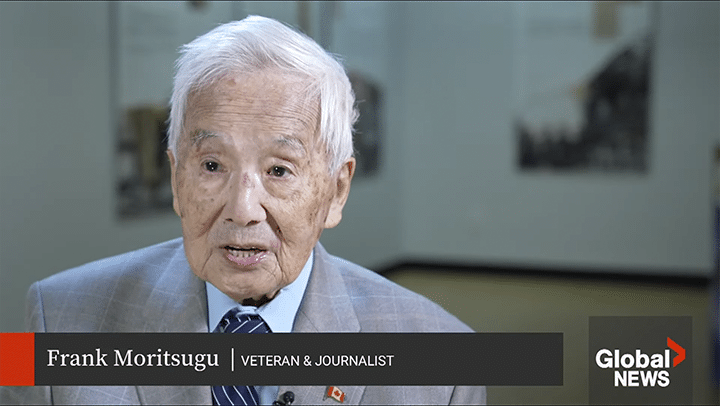

The President was Shigetaka Sasaki, and an Executive Committee was formed that included Vice-President Masatoshi Umetsu. Secretary General Frank Moritsugu, Treasurer Mitsuyuki Sakata, and four others: Frank Hatashita, Genichiro Nakahara, Shigeo Nakamura, and George Tsushima. All the men were at least 2nd Dan black belts.

When the group sought the charter, they had to apply under a name different from that which Gauthier had used, and Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association (CKBBA) was the name selected. A Canadian-wide judo organization was born in 1956, but without the word “Judo” in its official title.

It was about this time (circa 1957) that the language of the meetings was changed from Japanese to English. This was necessary as all black belts had equal voice at the annual meetings, and the trend was that more and more black belts would be non-Japanese. The changeover also made the CKBBA more credible to the IJF and as it turned out, to the Canadian Olympic Association (COA). »

For more history :

Atsumu Kamino & Etsuji Morii

Etsuji Morii

Atsumu Kamino and Doug Rogers

Frank Moritsugu

Risei Kano

Toshirō Daigo

Kodokan

IJF

Canadian Olympic Committee

Judo Ontario

Provincial associations

Frank Hatashita

Mikinosuke Kawaishi

Robert Arbour

Marc Scala

Bernard Gauthier

1956 World Championships in Tokyo

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

Canadian Kodokan black belt association : You are currently on the Canadian Kodokan black belt association, now known as Judo Canada. Please take the time to browse the website and enjoy learning the many roles a judoka can explore in his journey and discover the many events in Canadian judo.

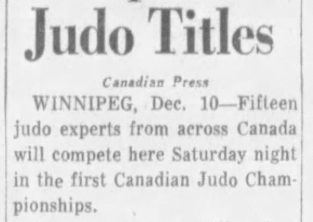

1959

First all Canadian Judo Championships held in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Fred Matt of B.C. became the first national champion & Elaine McCrossan was the first women in Canada to be promoted to black belt .

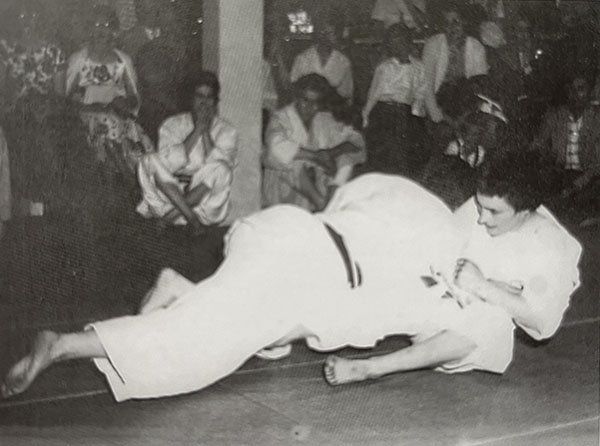

1st International competition for women at Hatashita Dojo.

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

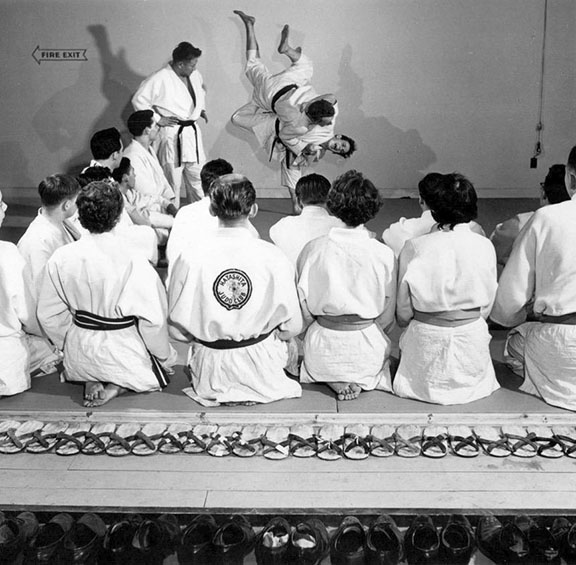

« NO weight Classes !

Having won sole affiliation with the International Judo Federation, the CKBBA now set about organizing a country-wide championship in order to select possible entries into the World Judo Championships. The first such Canadian Championships were held in 1959 in Winnipeg. There were about 3,500 judokas in the country at the time, and of these, there were 188 black belts.

There were no weight classes in these first national championships. Everyone fought in the same division and only one champion was declared. »

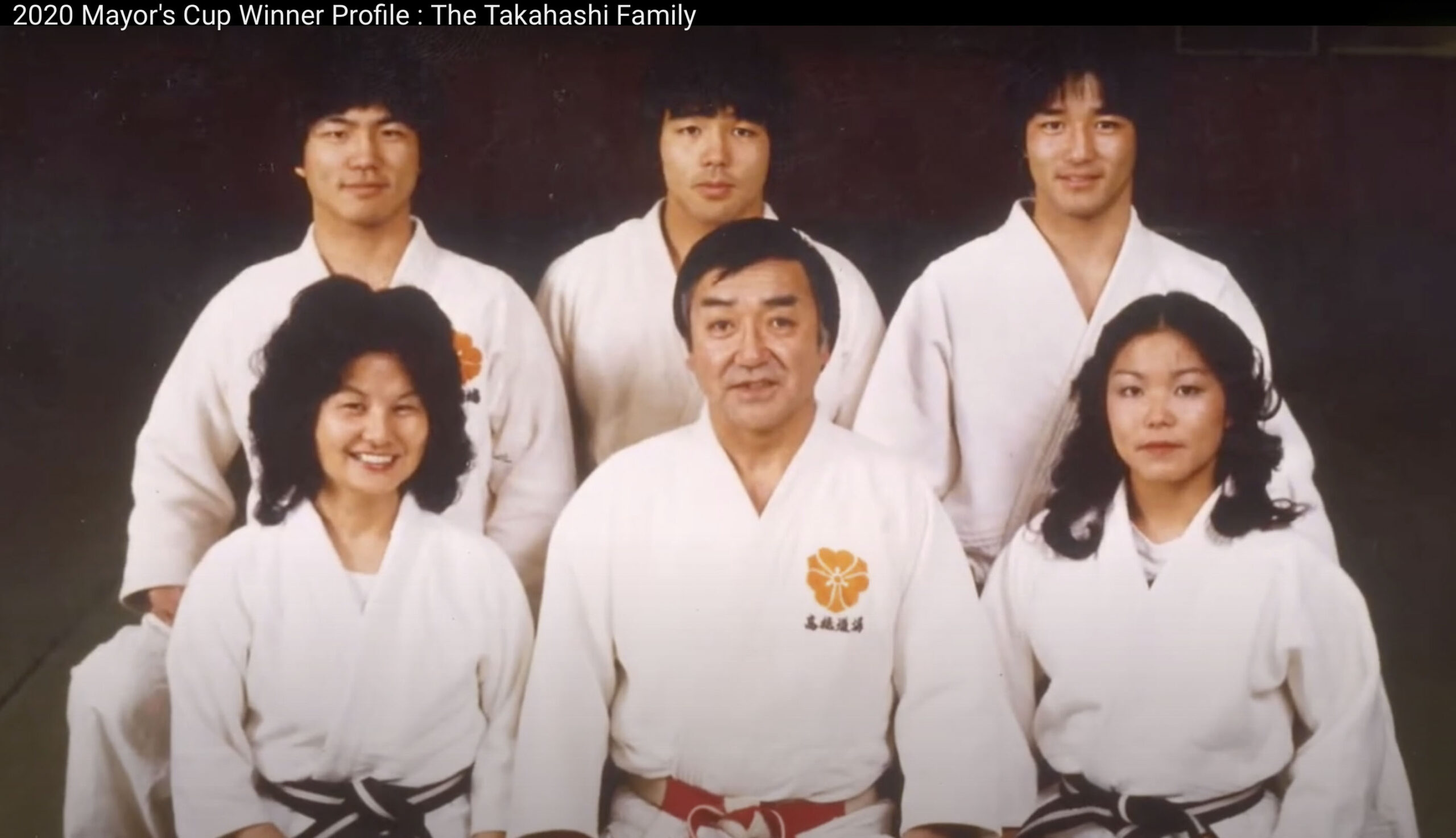

«The winner was Fred Matt (3rd Dan) from Vancouver. One of those Matt defeated in the preliminaries was Masao Takahashi, whose son Phil would later become one of the few Canadian judokas to win a world championship medal. As a true Canadian Champion, Matt represented Canada at the Pan-American Championships in Mexico that same year. There he won gold medals in both heavyweight and open divisions. »

« Women in Judo

While the men were busy in the boardrooms and organizing their first national championships, oblivious to them, the women were quietly ma king their own history. The year 1959 was significant on two accounts – the very first international tournament for women was held at the Hatashita Dojo in Toronto, and Elaine McCrossan passed the Ontario Judo Association’s November black belt grading exam to become the first Canadian female to be promoted to 1st Dan. In Quebec, Céline Darveau, one of the first women to earn her black belt, also became the first Canadian female referee. »

« If there was one contribution to the sport of judo from the Western World, it was the early acceptance of women into the competitive aspect of the discipline. The first Women’s Canadian Judo Championships were held in Montreal in 1976: the first World Judo Championships for women were held at New York City in 1980: the first World University Championships for women were held at Strasbourg, France, in 1984: and after being a demonstration sport in the Seoul Games, women’s judo became a full-fledged Olympic event in the Games of the XXVth Olympiad in Barcelona, Spain.

Keiko Furuda (1913-2013) was well known throughout the world for her expertise in katas. She gave several clinics in Canada during the 1960 and 1970’s. She was the granddaughter of Hachinosuke Fukuda, one of the men who taught Jigoro Kano the art of jujitsu. All her life, she traveled the world and teach kata. Her last visit to Canada was in 1997. Fukuda-sensei was the highest-ranking female judoka in the world at 9th Dan. »

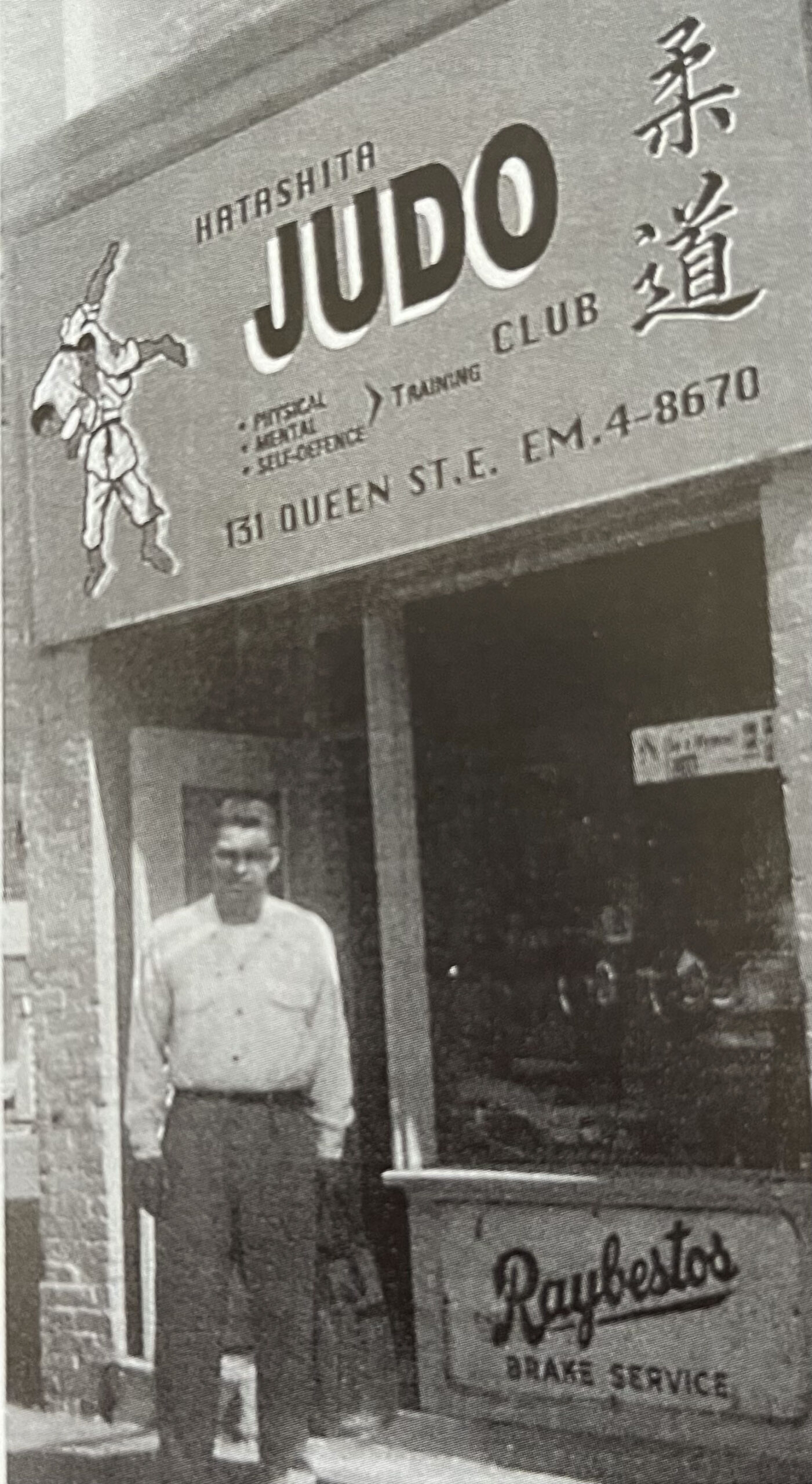

The Hatashita Dojo and it’s founder Frank Minoru Hatashita

Hatashita relocated to Toronto after the war and willingly put in the time under poor conditions, in humble surroundings, to establish his own dojo. Possessed of a strong will and spirit, Hatashita the sensei developed many top judokas in Canada. The Toronto Hatashita Dojo became famous in Eastern Canada and the Mid-Western States for its five-man judo teams during the 1950s and 1960s, winning title after title.

Most judo sensei were, and are, volunteers. Frank Hatashita saw some business potential in dojo ownership and turned his club operation into a full-time business. A precarious step at the time, but he ran it for 47 years. And from the Toronto bas Hatashita organized satellite dojos in other cities right across Ontario. In total he sponsored close to 100 satellite clubs.

Being his own boss, he could also devote time to the organization and development of judo not only in Canada, but throughout the world. A charismatic leader, he became known internationally as “Canada’s Mr. Judo.” In 1961 he succeeded Masatoshi Umetsu, becoming the third president of the CKBBA, and served in this capacity for the next 18 years. He also became President of the Pan-American Judo Union wich governs judo throughout the Americas serving four terms. As well, he was one of five vice-presidents of the International Judo Federation.

Little was known of the sport of judo outside of the Japanese Canadian communities before Frank Hatashita. He changed that. He brought judo to the people. He wrote articles for the newspapers. He published a monthly Canadian Judo News Bulletin. He put on countless demonstrations and clinics. And when the Canadian Olympic Association contemplated a 1964 Olympic team without a single judokas, Frank went on a publicity campaign to get Doug Rogers named to the team. Judo in Canada would not be where it is today without Frank Hatashita. Above anything else, Hatashita sensei loved to teach judo. Every day of the week.

While is decisions as president were not without some controversy, no one could question his dedication and lifetime of service to judo in Canada. Frank Minoru Hatashita was inducted into the Judo Hall of Fame in 1996 and was the first Canadian to be promoted to 8th Dan.

Frank Hatashita died in 1996, but his presence can still be felt all around America with the martial arts equipement company bearing his name. It is lead in the United Staes by his daughter, Lia, and in Canada by his nephew, Roman.

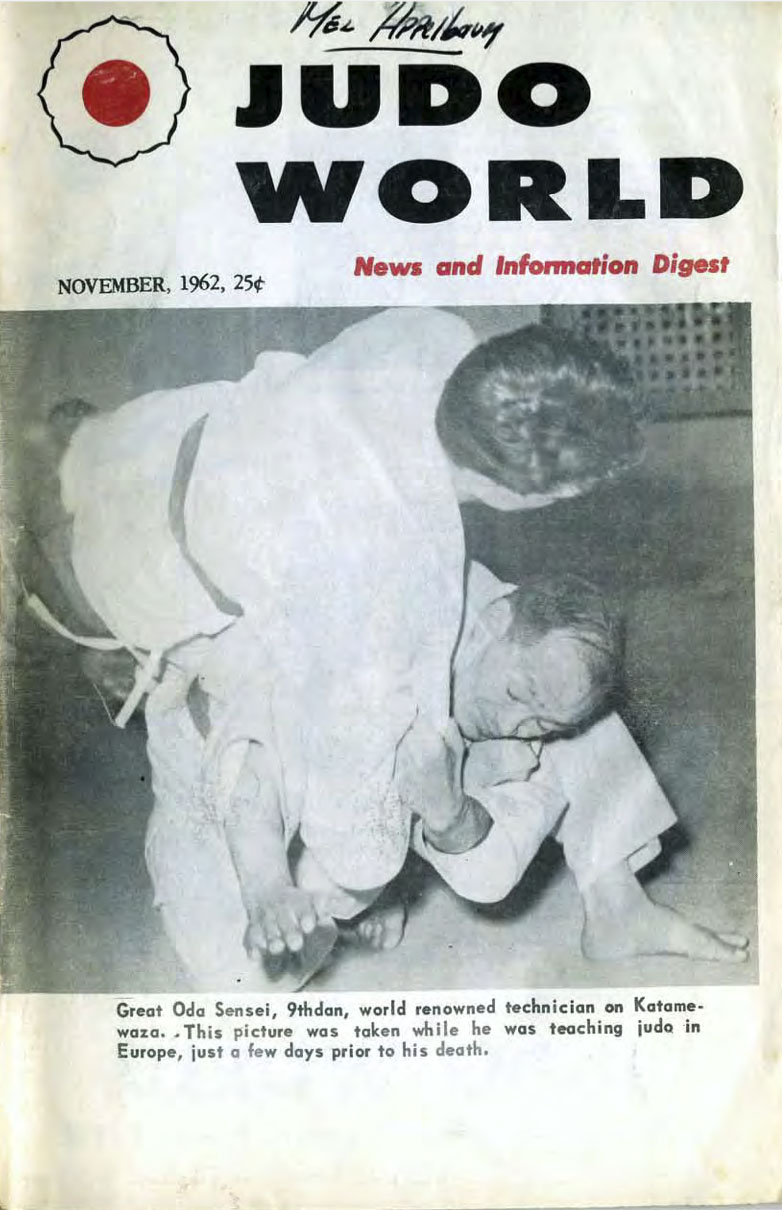

Frank Hatashita was a real entrepreneur and promoter of judo. In 1959 he established the Judo News Bulletin. The name changed to The Canadian Judo News in 1960, with photos appearing on the front cover in 1961. In July of that same year the name was changed to Judo World. The subscription rate was 3$ per year.

For more history :

Fred Matt

Céline Darveau

Hakudokan

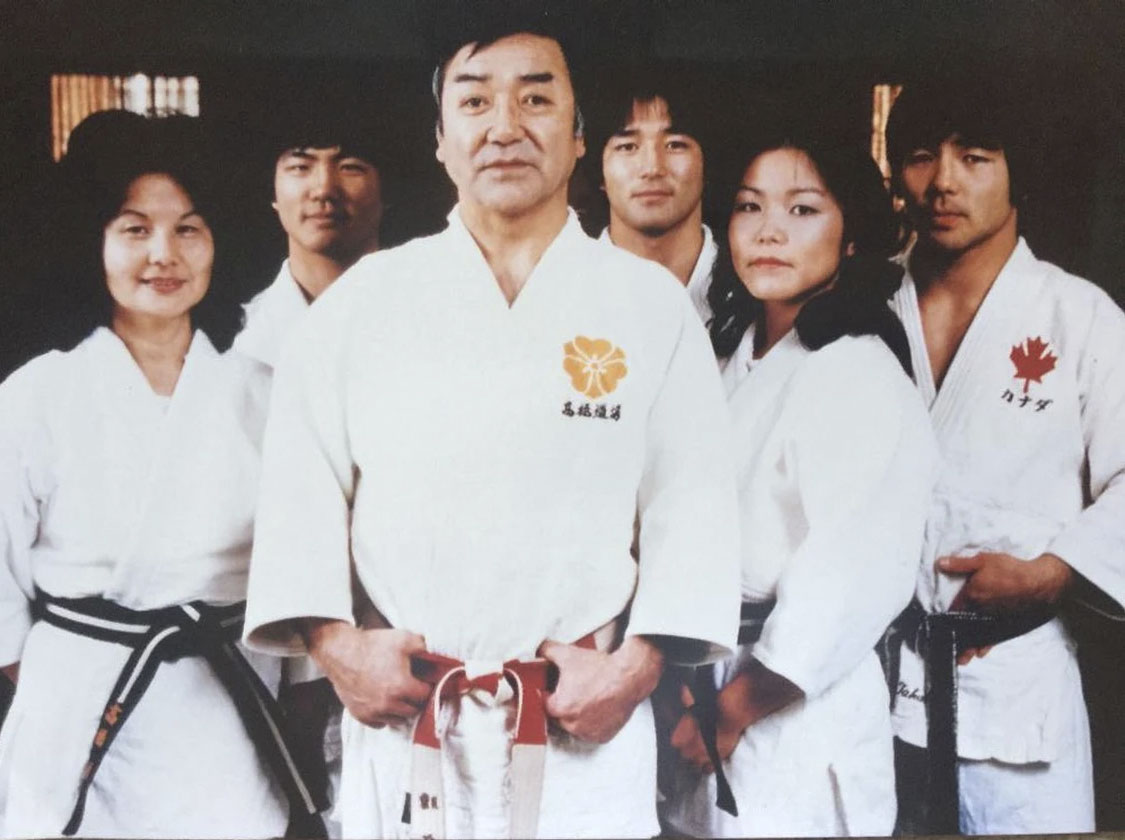

The Takahashi Family

Masao & Phil Takahashi

Phil Takahashi

Takahashi Dojo

Keiko Fukuda

Hachinosuke Fukuda

Frank Minoru Hatashita 1968

Judo World 1962

Masatoshi Umetsu

Pan-American Judo Union

Hatashita Judo Open

Peterborough Hatashita Judo Club

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1964 - 1965

1964 – Judo joins the Olympic Games in Tokyo and Doug Rogers wins a silver medal and becomes Canada’s first Judo hero.

1965 – Doug Rogers wins the first medal (bronze) for Canada at World Championships

Excerpt from Canada’s Sports Hall of fame web site :

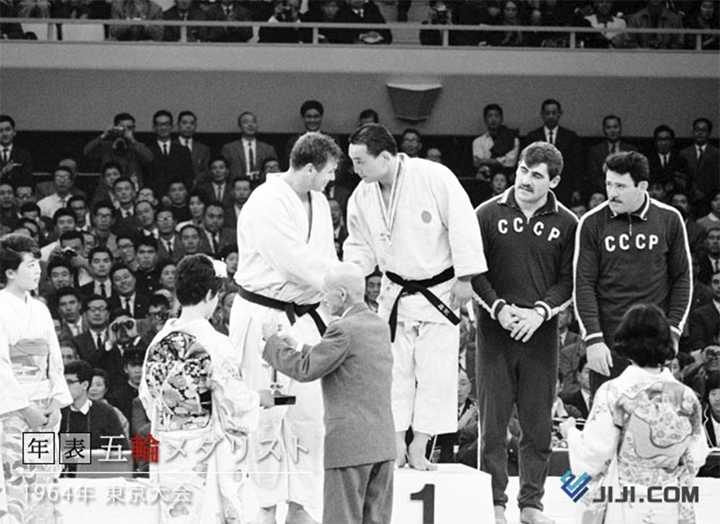

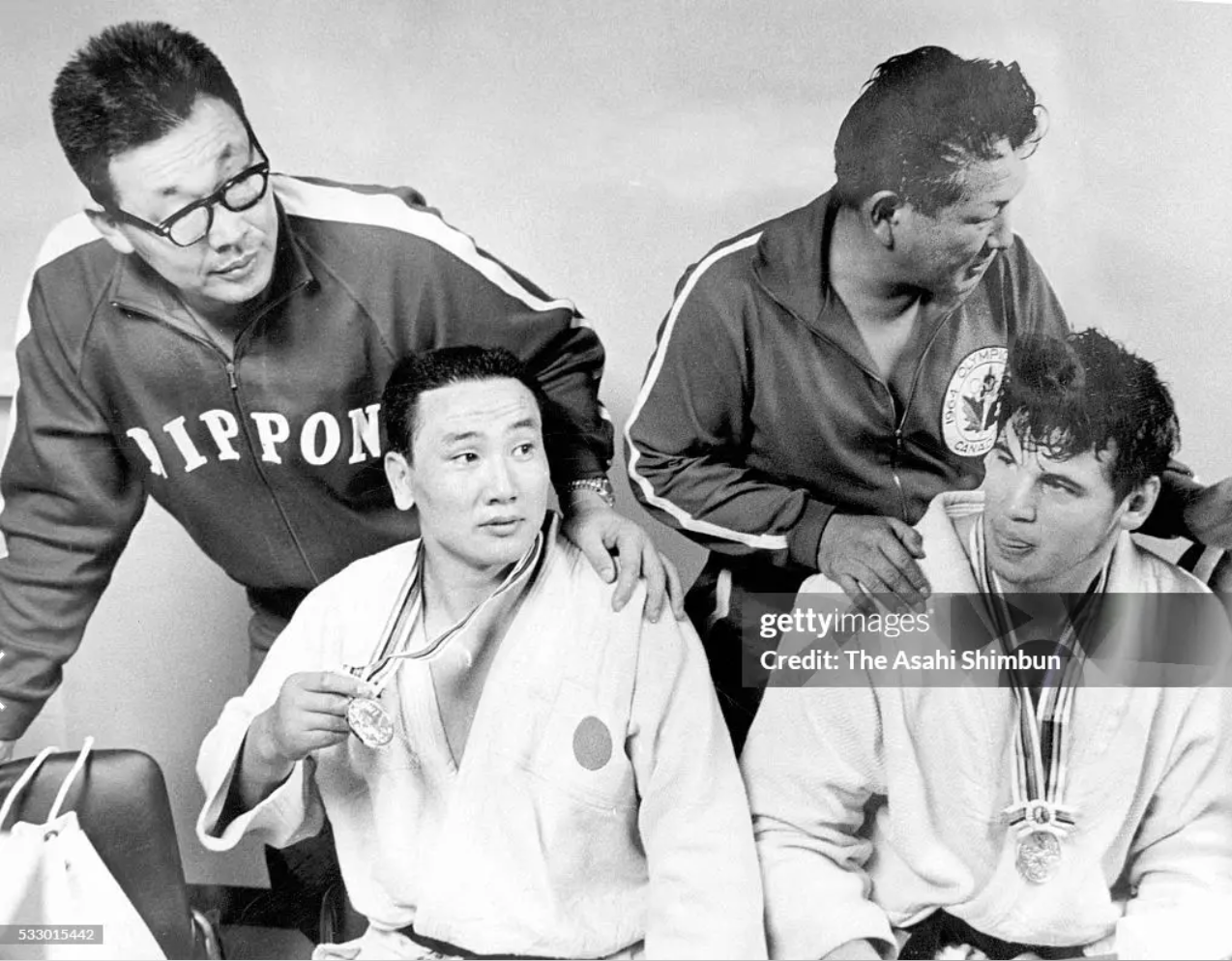

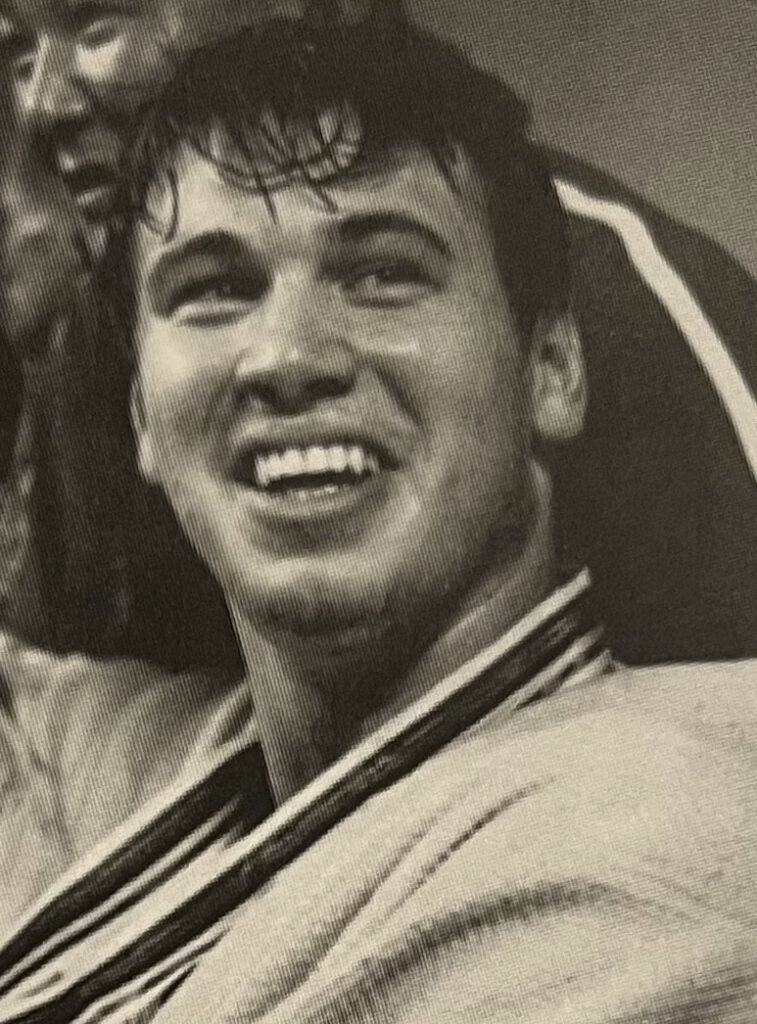

« After three-and-a-half years in Japan, Rogers had become an accomplished judoka and was selected to Canada’s 1964 Olympic team. Rogers was the dominant figure in Canadian judo in the mid-1960s, winning the national heavyweight championship four years running from 1964 to 1967.

But it was back in Japan, at the 1964 Olympic Games, that he made his mark on the international scene. In the semi-finals of the heavyweight competition at Tokyo’s Budokan, Rogers won a clear decision over the competitor from the Soviet Union.

Only ten minutes later, however, he was back to face Japan’s famed champion Isao Inokuma. They had trained against one another at the Kodokan. Neither judoka was able to score a decisive victory and Inokuma was awarded a close decision, with Rogers settling for a silver medal. After the Olympics, Rogers remained in Japan to train full-time with sensei Kimura at Takushoku University. Despite his 1964 Olympic success, 1965 was perhaps the greatest year of Rogers’ competitive career. »

For more history :

Judoka

Video Collection of National Film Board

Hall of Famer

Doug Rogers

Inducted in 1977

Alfred Harold Douglas ROGERS

Mr. Rogers was inducted as an athlete into Judo Canada’s Hall of Fame in 1996

Isao Inokuma Olympic 1964

TOKYO, JAPAN – OCTOBER 22: Gold medalist Isao Inokuma (L) of Japan and silver medalist Doug Rogers (R) of Canada attend a press conference after the Judo Heavyweight gold medal match during the Tokyo Summer Olympic Games at the Nippon Budokan on October 22, 1964 in Tokyo, Japan. (Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images)

Isao Inokuma – Judo Info

Tokyo’s Budokan

Nippon Budokan

Sensei Masahiko Kimura

Takushoku University

Kodokan Judo Institute

Team Canada

1964 Olympic Judo

British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame

1968

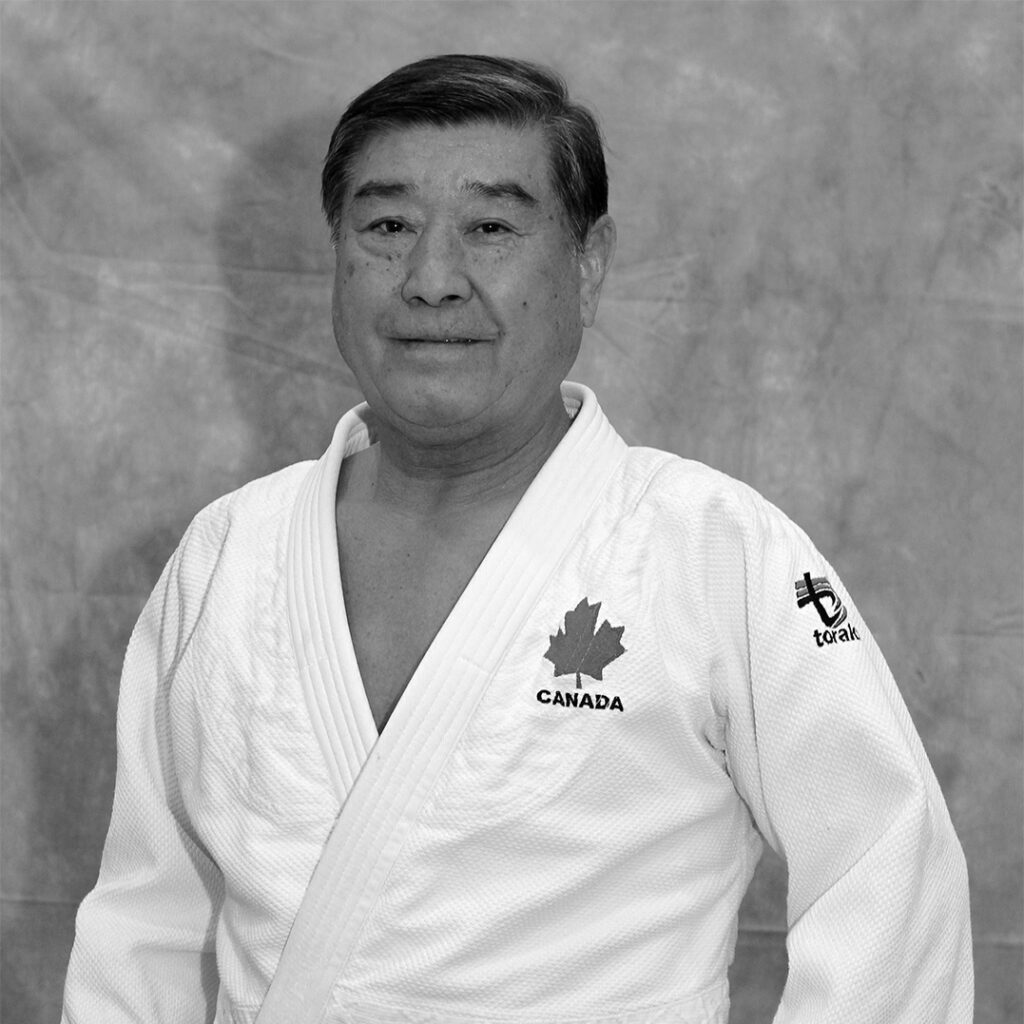

Hiroshi Nakamura arrives in Montreal from Japan, he became one of the most successful coach in the history of Judo In Canada and in 2019 is inducted by the COC Hall of fame

From the Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame Order of Sport :

An iconic mentor, trainer, and high performance coach who has devoted much of his life to developing judo in Canada, he continues to empower generations of athletes to fulfill their potential.

Hiroshi Nakamura has devoted much of his life to developing judo in Canada as an esteemed mentor, trainer, and high performance coach. Born in Tokyo in 1942, Hiroshi began practicing judo at the age of twelve, working with off-duty police officers at the Yanaka Police Dojo before attending the prestigious Kodokan Institute. One of only five Canadians to achieve the rank of Kudan (9th dan), Hiroshi ranked (by Black Belt Magazine) in the top 10 Japanese judokas (all categories) before injury cut his competitive career short. Becoming a dedicated trainer and coach, he began working with international athletes to prepare for the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, the first year judo was included as a full Olympic sport. One of the judokas who trained with Hiroshi before reaching the podium that year was Canadian Doug Rogers, who claimed a Silver medal in the Olympic heavyweight division. Recognizing Hiroshi’s exceptional devotion, Rogers seized the moment and asked him to travel across the Pacific to establish a national training program that would give Canadian judokas unprecedented access to competitive training in their own country.

When Hiroshi moved to Canada in 1968, he committed to a bold vision of making judo as popular as ice hockey across the Great White North. Settling in Québec, where the sport had few practitioners, Hiroshi began offering lessons at Vanier College in Montréal while giving free demonstrations in the cafeteria at lunchtime to spark student interest. In 1973 he opened his own dojo, the Shidokan Judo Club, in Montréal. Under Hiroshi’s guidance the Shidokan became the most successful competitive judo program in Canada and remained home to the National Training Centre until 2014.

Securing his legacy as the most important individual contributor to Canada’s presence in international judo, Hiroshi coached Canadian judokas at 13 International Judo Federation World Championships between 1969 and 2007 and served as coach of the Canadian judo team at five Olympic Games between 1976 and 2004. Many of his protégés have also become vital leaders in the sport, including CEO and High Performance Director of Judo Canada, Nicolas Gill.

An insightful, compassionate mentor, Sensei Nakamura has helped generations of athletes at all skill levels cultivate values that transcend sport, building a foundation for success on and off the judo mats. Emphasizing self-discipline, humility, and perseverance, he patiently encouraged each judoka to fulfil their own unique potential, empowering them to aim high and focus on kaizen, or continuous improvement. Deeply committed to students in his care, before funding was available for the national training program, Hiroshi regularly opened his home to young athletes who would move across Canada to work with him. Continuing to train future Olympians at the Shidokan today, Hiroshi has also used his expertise to help others by teaching women’s self-defence classes, offering judo programs for at-risk youth, and supporting young judokas in need of financial assistance through the Nakamura Gill Foundation.

For more history :

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame Order of Sport

CBC

Team Canada

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Sensei Hiroshi Nakamura Induction Speech

Coach, 2013 Geoff Gowan Award Winner

Judo Canada video demonstration series by sensei Hiroshi Nakamura

Kodokan Judo Institute

Vanier College

Sportcom

Shidokan Dojo

National Training Centre

Black Belt Magazine

Judo Canada Team Training 1975 Part 1

Judo Canada Team Training 1975 Part 2

1972

In Munich, Raymond Damblant became the first Canadian to referee at the Olympic Games.

From the Panthéon des sports du Québec website:

“French of origin, born in January 1931, Raymond Damblant is a physical educator, state certified in combat sport, who has practiced judo on four continents and taught this sport on three of them.

He was a member of the French team during three international meetings in Sweden, England and Spain before heading to Yugoslavia to join a team of teachers and develop judo in that country.

Despite a serious training program, I competed in three French championships without earning a title, not even any consolation! However, I reached the quarterfinals twice and the semi-final once,” underlines Raymond Damblant. On the other hand, at a time when weight categories did not exist, he won the national spring cup, a competition open to everyone except national medalists, and a good fifteen various meetings.

In 1959, Raymond Damblant received an offer and opted to come to Canada. He himself describes his departure for Canada as a risky adventure, since he had neither firm contract nor guarantee. He won the provincial championship and finished third at the Canadian championship.

It is not his exploits as an athlete that allowed him to enter the Quebec Sports Hall of Fame, but rather his involvement and the determining role played in the development of judo here.

Ninth dan in judo, as technical director of the Hakudokan judo club, he has trained more than 210 black belts on three continents.

Raymond Damblant was the founding president of Judo Québec in 1966, a position he held until 1971 before becoming the technical director of the organization until 1975. Responsible for combat sports at Expo 67, he acted as director of competitions during the Olympic Games in Montreal in 1976 and played the same role during the Olympic Games in Los Angeles in 1984.

In 1967, he became the first Canadian to receive the title of international referee at level A, which led him to referee at five world championships, nine Pan American Games and be selected as referee for two Olympic Games, those from Munich in 1972 and from Moscow in 1980.

He was also involved in Judo Canada, first assuming the vice-president from 1963 to 1970, the presidency of the grades committee from 1972 to 1989 and that of the technical committee from 1982 to 1986. Subsequently, he became general secretary of the organization from 1987 to 1996 before being named a life member in 2000.

Raymond Damblant adds to his already busy career the technical direction during three Canada Games in 1982, 1986 and 1990 and can be delighted to have played the role of chef de mission for Judo at the Olympic Games in Seoul and Barcelona and at four World Championships and two Pan American Games.”

For more history :

Panthéon des sports du Québec

Quebec Sports Hall of Fame

Hakudokan

IJF

37e Gala Sports Québec 2009

37th Gala Sports Quebec 2009

NFB

Judo Québec

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 1

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 2

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 3

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 4

Martialement vôtre

RDS broadcast

RDS broadcast showing Judo

1976

Montreal Olympics Games & the first edition of a women national championships

Excerpt from the Canadian encyclopedia :

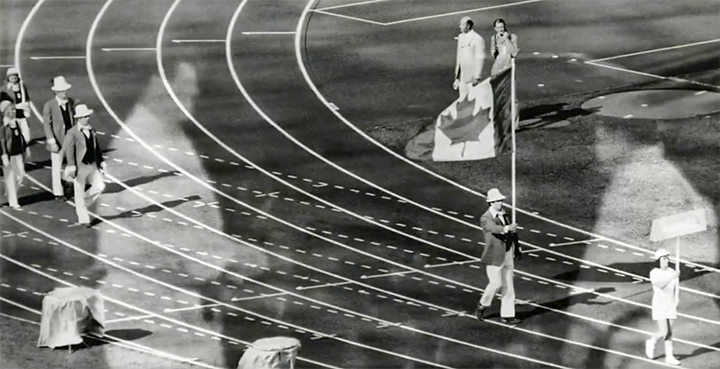

On 17 July 1976, at 3:00 p.m. more than 73,000 people gathered in the Olympic Stadium to take part in the Opening Ceremonies of the Montréal Olympics. The rituals began with the arrival of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, accompanied by Prince Philip and Prince Andrew and by IOC president Lord Killanen and Commissioner of the Games Roger Rousseau.

This was followed by the procession of athletes into the stadium. After the Queen officially opened the Games, the Olympic flame was carried into the stadium by two 15-year-old athletes, Sandra Henderson from Toronto and Stéphane Préfontaine from Montréal, to the sounds of the Olympic Cantata written by Louis Chantigny.

Excerpt from JOURNAL YUDANSHA of December 2006 :

It has been 30 years since women first competed at the Canadian National Championships. At the 2006 Senior and Juvenile/Junior Canadian Championships, it was time to reflect and honor our past. There we recognized the contribution of so many over the past 30 years and considered what the future might hold. Canadian females have gone from participating at small regional judo club tournaments to, not only participating in the past 30 Canadian Championships, but also at many international tournaments around the world, including the Olympics since 1988.

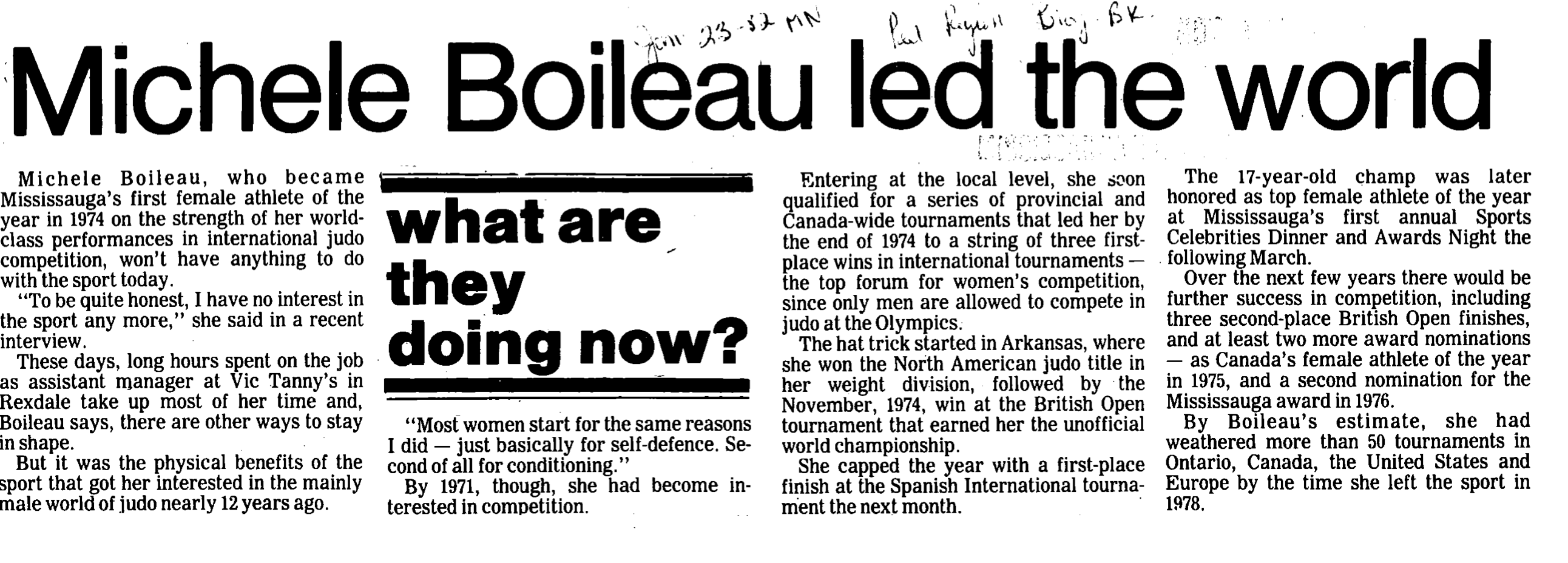

In Lethbridge, AB, during the opening ceremonies of the Juvenile and Junior Nationals, Judo Canada honored all of the original 1976 National women’s champions, Monette Leblanc, Diane Hardy, Sue Gribben, Lorraine Methot, Yvonne Lestrange, Michelle Boileau and Tina Takahashi by presenting each of them a beautiful, framed certificate by Judo Canada.

The Yudansha newspaper: Former Judo Canada newspaper which appeared 2-3 times a year, from 1983 to 2007.