Where to go for the points, how to adjust…

29 December 2006Judo as Self-Defence – Mental and Physical Reflex

29 December 2008Bernard Letendre

Head of Wealth and Asset Management, Canada

Manulife

Bernard Letendre has been practicing judo for almost 37 years and trained for 30 years at Club Hakudokan in Montreal with Sensei Raymond Damblant, 9th dan. Bernard holds a third degree black belt (Sandan) and teaches judo at the University of Toronto Judo Club. Outside of the dojo, Bernard brings 23 years of experience in the financial services industry to his role as Head of Wealth and Asset Management, one of the largest invest firms in the country. Bernard holds a Bachelor and a Master’s degree in law from the University of Montreal, is a member of the Quebec Bar and is a published legal author. He is a Director of the Investment Fund Institute of Canada (IFIC) and has held Board positions with a number of high-profile non-profit organizations including the Les Grand Ballets Canadiens de Montreal, the National Gallery of Canada Foundation and La Fondation du Dr. Julien. He lives in Toronto with his wife and three children.

Someone to whom I owe so much

I am extremely fortunate that life has put so many good role models on my path over the years. Whether professionally or otherwise, I clearly wouldn’t be where I am today if it wasn’t for the people who have, throughout my life, guided me along in one way or another.

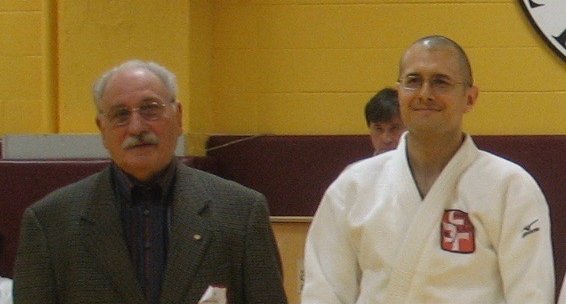

One of those people has played a very unique role in shaping me into the person that I have become: My judo teacher of almost forty years, Sensei Raymond Damblant.

Mr Damblant is no longer a young man and his impressive martial arts career spans longer than most of us have been on this Earth. When I first met him in my early teens, he must have been about the same age I am today.

He was never big on ceremony and lest any martial artist reading these lines be offended by the apparent lack of formality, let me clarify that nobody at our dojo ever addressed him as “Sensei”, even though few people that I can think of are more deserving of the title than he is. From the time I started learning judo at his school decades ago, I always knew him as “Mr Damblant” (Monsieur Damblant in French) and that is how I address him to this day, with great respect and affection.

Mr Damblant is not a boastful person and, in all the years he taught me judo, he never talked about his remarkable accomplishments. Those were the days before the advent of the Internet and back then, we couldn’t just google people to find out more about them. What I gradually learned about him over the years, I discovered almost by chance, often through the eyes of an admiring teenager.

In his youth, before coming to Canada, he had been in the French Army. He was clearly a well-traveled man, even though I couldn’t understand back then why a simple judo teacher would be jetting around the world constantly as he did. He was also a very learned man who could engage with people in French, English, Spanish and Arabic, and I believe I might have overheard him on the phone once or twice speaking Japanese. To a young person, this was all very impressive.

We all knew that he owned a business because it was located just next door to the dojo. From the neighborhood where I knew he lived and the kind of car I knew he drove, I deduced early on that he must have been a successful businessman. We also knew that his school was open to all and that nobody ever got turned away because they weren’t able to pay.

None of that really explained why coaches, instructors and referees from all across the country would treat him with such great deference whenever he accompanied us at tournaments and for a long time, I was quite puzzled by this.

Indeed, it was many, many years before I eventually learned that he had helped run the Olympics in Montreal, was competition director for judo at the Los Angeles Olympics and held at one point the highest possible rank an international referee can achieve. Now holder of a very rare and prestigious 9th degree black belt in judo, he also holds very high ranks in many other martial arts, a fact that stunned me when I found out about it as an adult, many years later. Mr Damblant, as you can plainly see, is a well-rounded person who has had much success in many aspects of his life. One can indeed strive to excel on many fronts and that lesson was not lost on me as I was growing up.

Most of what I have learned from Mr Damblant, I have learned from taking stock of what is possible for someone like him to accomplish, and from just spending time in his presence, observing him up close: How he talks, how he handles himself inside and outside of the dojo, how generous he has always been towards so many people young and old, how patient he was with us when we were turbulent teenagers, how polite he always was to our parents and other adults. That such an accomplished person would have remained so kind and humble is a life lesson in itself.

The following example will illustrate what I am talking about:

During tournaments, when other coaches and instructors would yell instructions at their athletes throughout their fights, Mr Damblant would sit quietly in the coach’s chair, speaking to us only occasionally when the referee called for a pause in the fighting, always in a controlled tone. After our fights, when appropriate, he would take us aside and give us a few pointers in private so that we could do better in the future.

When we won, he would congratulate us in a calm and dignified way, while some coaches went into boisterous displays for their athletes. When we lost, he would ask us if we had fought to the best of our ability and offer a word of encouragement, never giving any sign of disappointment, while some coaches reprimanded their athletes in plain view for not doing well enough.

In this way, Mr Damblant helped us build our confidence and made us want to persevere and continue to improve ourselves. He also gave us a powerful model for how to always treat others with respect. It’s not surprising then that over the years, he has helped almost 300 people – men and women, and people from all sorts of backgrounds – to obtain their black belts and that many of his students have gone on to achieve very high ranks and open their own successful schools.

Mr Damblant stands for me to this day as a towering model of dedication, excellence, respect and quiet dignity. When I step onto the mats, he is the person that I try to emulate; not so much from a technical standpoint because his knowledge of judo far exceeds my own. But I do try to guide my conduct on his, and behave in a way that would make him proud if he were able to see me. And on those occasions over the years when I have not lived up to the standards that he has himself always maintained in our presence, I have been inspired, by his example, to strive to do better going forward.

A few weeks ago, having already been honored by the International Judo Federation and the Panamerican Judo Union, Mr Damblant was honored by Judo Canada for his life’s work at a ceremony that probably made him uncomfortable and which I was unfortunately unable to attend. What precedes is the tribute I would have paid him had I had the chance to take the podium to honor him publicly at that event.