Judo Canada

1924 -2024

Dear Judo Canada members

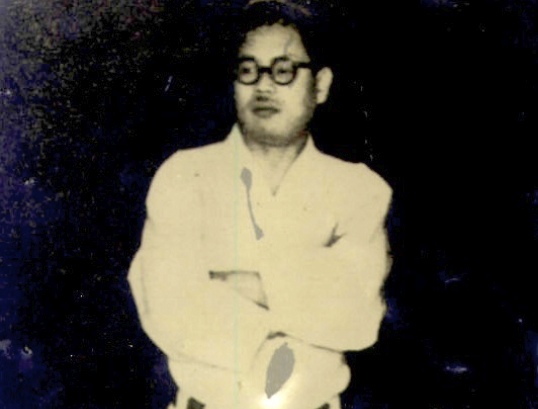

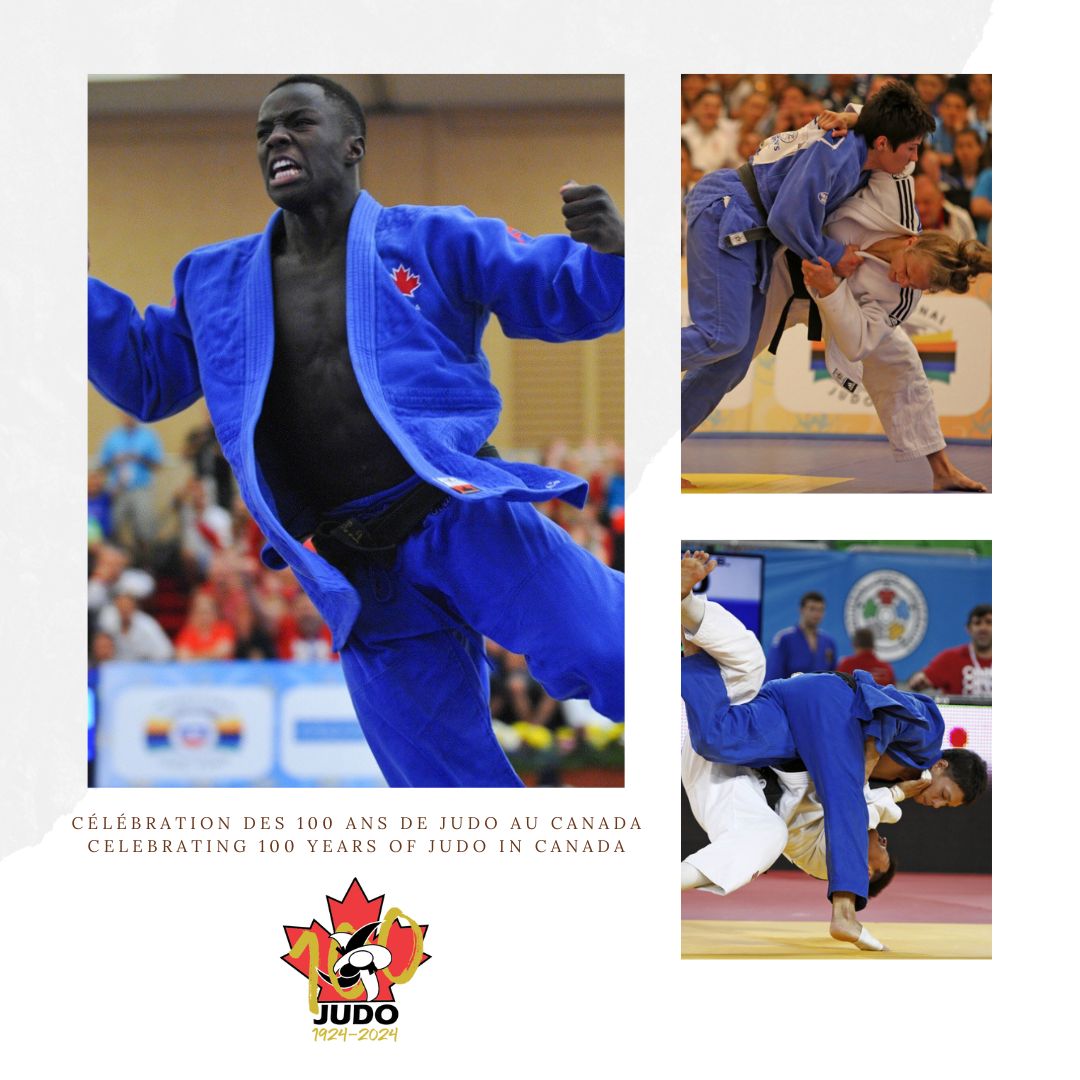

2024 is the 100th anniversary of organized Judo in Canada, which began with the establishment of Tai Iku Dojo by Shigetaka ‘Steve’ Sasaki in Vancouver in 1924.

Judo Canada encourages all organizations, clubs, and individual judoka to support the 100 campaign that we will celebrate.

1924

Foundation of the 1st permanent Dojo Tai Iku

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

“As the “father of Canadian judo,” Steven Shigetaka Sasaki deserves special mention in any historical work devoted to the sport…”

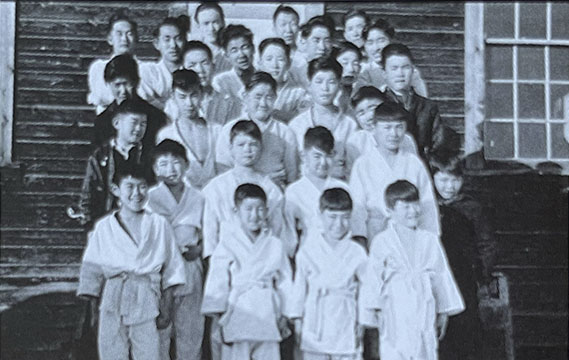

“Shigetaka Sasaki arrived in Canada in 1922 with the rank of 2nd dan. In Japan, he taught judo at Yonago High School. Although he recognizes a certain practice of discipline in British Columbia, he judges that teaching is done haphazardly. So he brought together the Japanese community in Vancouver to gauge interest. Over the course of a year, Sasaki plans, organizes other meetings, forms a stakeholder group and solicits sponsors. In 1924, he opened his first dojo.

As with any business started from scratch, things don’t go smoothly. First you need to find a training room. At the beginning, the lessons were given in the high-ceilinged living room of one of the sponsors, Mr. Kanzo Ui. It is not known whether the latter follows the lessons himself. The house is located at 500 Alexander Street in Vancouver. The tatami mat was purchased with money raised by another sponsor, Mr. Ichiji Sasaki, owner of a sushi restaurant. The Vancouver Tai Iku dojo was born.”

The expansion

Mr. Ui’s living room does not house the Tai Iku dojo for long. In a few months, so many Vancouverites of Japanese origin registered that we had to find new premises. What is done, Powell Street.

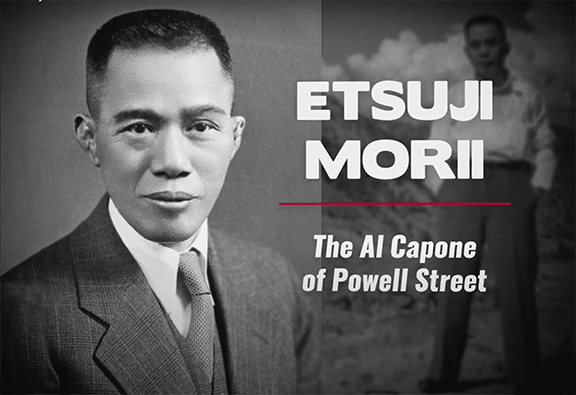

It costs $0.30 for adult students, $0.10 for boys and $0.05 for girls to attend the dojo. We do not know today whether this rate is then charged per session, per week or month. One thing is certain, income is so minimal that Sasaki has to dip into his personal money to pay running costs, rent, electricity and water. Far from being profitable, the company would probably founder without the sponsors who end up assuming part of the financial burden. Among them is the club’s main benefactor, Etsuji Morii, businessman and judoka.

The same “no-profit” scenario will repeat itself throughout this period of expansion. The roots and development of judo are accomplished for pleasure. Not only do teachers or masters, one after another, spread “the good news” voluntarily, but they even have to pay out of their own pockets for this privilege, as demonstrated by the adventure of Shigetaka Sasaki in establishing the first permanent dojo. No doubt they are then carried by the spirit of seiryoku zenyo and jita kyoei – maximum efficiency and mutual prosperity.

In 1927, another club was founded in Steveston, British Columbia. The instigators of the project, Tomoaki Doi, director of the youth program and judo teacher, and Mr. Takeshi Yamamoto seek Sasaki’s help. Despite the busy schedule of running his business and leading a fledgling organization, Sasaki travels to Steveston twice a week. The Steveston dojo therefore becomes a subsidiary of the Tai Iku dojo in Vancouver. Other branches opened in Kitsilano, Fairview, Haney, Mission, Woodfibre and, on Vancouver Island, Chemainus, Victoria and Duncan. Sasaki tirelessly gets personally involved in teaching or persuades others to get involved. Whonnock and Hammond also have their dojo.

Among the senseis of the time were Atsumu Kamino (Kitsilano), Tomoaki Doi (Steveston), Masatoshi Umetsu (Fairview), Eiichi Hashizume and Yoshitaka Mori (Mission), Tomutsu Mitani and Kasuta Ryoji (Haney), Frank Mukai (Tai Uku ), Shigeo Nakamura (Duncan), Mitsuyuki Sakata and Genishiro Nakahara (Chemainus), Kametaro Akiyama (Victoria) and Satoru Tamoto (Woodfiber). For their part, all judokas are of Japanese origin, either isseis (born in Japan) or niseis (born in Canada to Japanese immigrants). But that will change from 1932.”

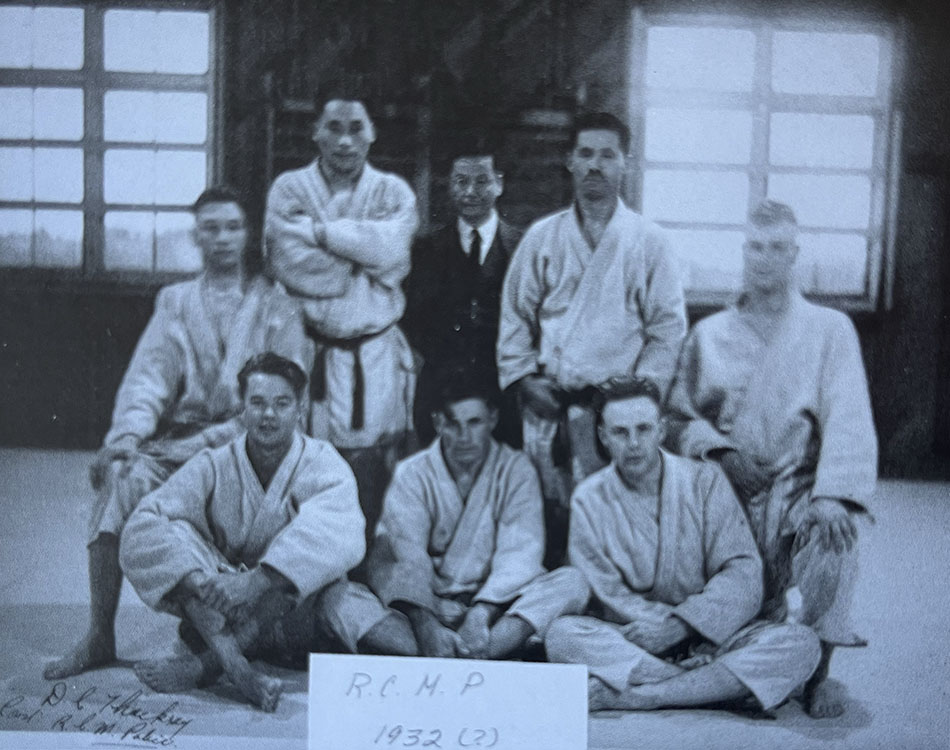

“The RCMP

The RCMP approached Shigetaka Sasaki in 1932, intending to introduce its officers to judo. Aware of the breakthrough his discipline could experience in the country thanks to this opportunity, Sasaki decides to take charge of officer training himself. A close relationship was then established between the sensei and the RCMP which would serve Sasaki on many occasions.

That year, in February, a judo tournament was held in Vancouver, attended by the director of the local RCMP detachment. The man was so impressed by the demonstration that he asked Ottawa for permission to replace boxing and wrestling with judo in the training of officers. With Ottawa’s blessing, we speak to Sasaki. This is how 11 officers began training twice a week at the detachment gymnasium, 33 Heather Street. This is probably the first time that judo has been taught to white people on Canadian soil. The same year, Sasaki went to Japan to study under Kyuzo Mifune, 7th dan in Kodokan and chief instructor. He is promoted to 3rd dan. »

For more history :

BC Sports Hall Of Fame

Judo British Columbia

Centre Nikkei Place – Japanese Canadian National Museum Newsletter ISSN#1203-9017 Summer 2002, Vol. 7, No. 2 – A History of the Steveston Judo Club by Jim Kojima:

The Steva Theatre mentioned in the newsletter A History of the Steveston Judo Club

Steveston Dojo now

Founded in 1944, the Vernon club is the oldest still in operation in Canada. Its founder, Yoshitaka Mori, was a former resident of Mission, (B.C.)

Vernon Judo Club Now

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1932

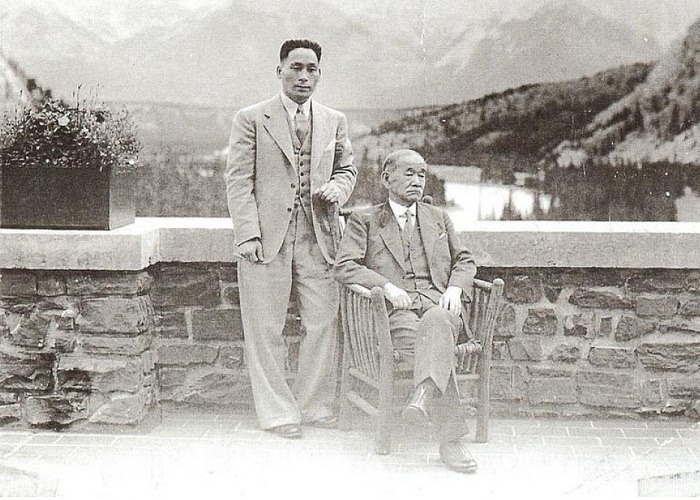

Master Jigoro Kano First visit to Canada

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

At the same time, the founder of Judo, Dr. Jigoro Kano, on his return from the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, visited the Tai Iku Dojo in Vancouver. He renamed the dojo Kidokan – “House of Intrinsic Energy”. All other dojos in B.C. became branches of the Kidokan. This was a great honour for the young club. Professor Kano added to the special occasion by granting honorary black belt status to the three members of the Vancouver Club: Eichi Kagetsu, Gentaro Isobe and Toshiaki Sumi. These were unique titles created by the Master because the three recipients had never competed in a tournement. They had given financially, mentally, spiritually and physically to the sport, and Professor Kano sought to recognize their contributions by this special status.

For more history :

Eikichi Kagetsu

Jigoro Kano visited Vancouver again in 1937 :

Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Center

Prince Chichibu’s visit to Canada 2

Shigetaka (Steve) Sasaki Family Fond

The Ocean liner seen in the video is Heian Maru and is the sister of the Ocean liner Hikawa Maru place of Master Jigoro Kano’s death

Hikawa Maru

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1956

Establishment of the Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association (CKBBA)

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

«In February 1942, the Federal Cabinet passed an act which launched a shameful period in Canadian history. Responding to paranoia, the government ordered the expulsion of some 22,000 Canadians of Japanese origin from their homes if they resided within 100 miles of the Pacific Coast. Seventy-five percent (75%) of the affected individuals were either born in Canada or naturalized. This order was not rescinded until March 31,1949, even though the war ended in August 1945.»

« Many are the stories of the beginnings of small clubs started selflessly by men who had learned their judo in B.C., nurtured it through wartime, and then established nuclei across the country like seeds blown from a plant. Each seed begot a mature tree which, in turn, produced more seeds and more trees.»

« Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association

When the judokas from B.C. began to roll into Toronto after the war, it was natural for them to look up old judo friends scattered as a result of the expulsion, and the easiest way to find those in the Toronto area was to visit Atsumu Kamino’s dojo in the basement of The Church of All Nations on the corner of Spadina and Queen. The dojo established in 1946, was named the Kidokwan Judo Institute after the original Vancouver Kidokan Club, which had been the headquarters dojo in prewar B.C. With so many judokas in one city, it was natural for Kamino, 3rd Dan at the time, and third-highest rank in Canada (to that of S. Sasaki, who was now residing in Ashcroft, B.C., and E. Mori), to organize these black belts and form an executive board to look after the business of judo, which included the granting of grades. Thus, the “ Canada Judo Yudanshakai “, the forerunner to the Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association, was formally established. But now occurs a strange step in the judo history.

The Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association, CKBBA, or what was later to become Judo Canada, was incorporated in 1956, but it was not officially recognized by the International Judo Federation until 1958. There was already another judo organization in Canada, founded by Bernard Gauthier. Gauthier was a self-taught expert with no connection with the Kodokan. His judo followed the Mikinosuke Kawaishi system, which he studied through books, and on weekends he travelled to Montreal to learn from Frenchman Marc Scala. Gauthier fought in the 1st Judo World Championships in Tokyo in 1956 representing Canada.

Earlier, in 1949, Gauthier, ever ambitious, applied to the Canadian Government for a charter to establish the Canadian Judo Federation (CJF), and in 1952 his fledgling organization set out to organize a number of Canadian Championships under the auspices of the CFJ. The first one was in 1952, and Gauthier got the Japanese embassy in Ottawa to sponsor it by donating the championship trophy. To add lustre, he invited the International President Risei Kano, son of Founder kano, and All Japan Champion Daigo to be present.

The second CJF-sponsored national tournament was held in Toronto in cooperation with the Kidokwan. Marc Scala, who had moved from Paris to Montreal in 1950 and was a disciple of Mikinosuke Kawaishi, took home the coveted championship plaque courtesy of the Japanese embassy. Frank Hatashita’s Toronto club won the team title, something they would do many times.

But for Atsumu Kamino, the symbolism of watching the plaque being taken away from those who had done so much for Canadian Judo, nursing it through the hard times, was too much to overlook. And when Gauthier represented Canada at the First World Championships in Tokyo, Japan, it hit too close to home.

The Toronto judokas, under the quiet leadership of Atsumu Kamino, then set about to correct the situation. They legally incorporated the existing Canada Judo Yudanshakai in order to give legitimacy to their own national organization. Letters patent for the newly formed organization were issued October 25, 1956.

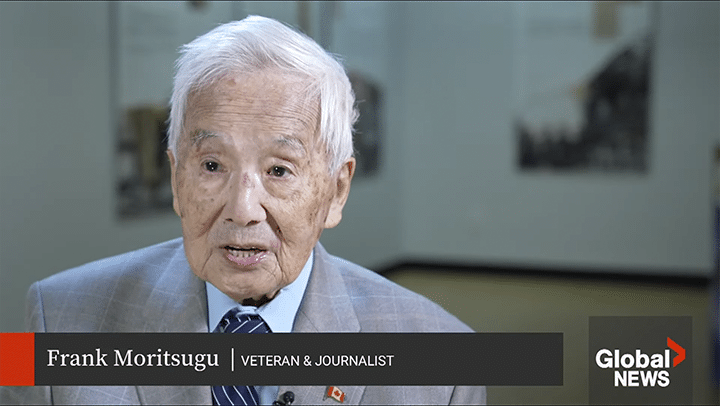

The President was Shigetaka Sasaki, and an Executive Committee was formed that included Vice-President Masatoshi Umetsu. Secretary General Frank Moritsugu, Treasurer Mitsuyuki Sakata, and four others: Frank Hatashita, Genichiro Nakahara, Shigeo Nakamura, and George Tsushima. All the men were at least 2nd Dan black belts.

When the group sought the charter, they had to apply under a name different from that which Gauthier had used, and Canadian Kodokan Black Belt Association (CKBBA) was the name selected. A Canadian-wide judo organization was born in 1956, but without the word “Judo” in its official title.

It was about this time (circa 1957) that the language of the meetings was changed from Japanese to English. This was necessary as all black belts had equal voice at the annual meetings, and the trend was that more and more black belts would be non-Japanese. The changeover also made the CKBBA more credible to the IJF and as it turned out, to the Canadian Olympic Association (COA). »

For more history :

Atsumu Kamino & Etsuji Morii

Etsuji Morii

Atsumu Kamino and Doug Rogers

Frank Moritsugu

Risei Kano

Toshirō Daigo

Kodokan

IJF

Canadian Olympic Committee

Judo Ontario

Provincial associations

Frank Hatashita

Mikinosuke Kawaishi

Robert Arbour

Marc Scala

Bernard Gauthier

1956 World Championships in Tokyo

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

Canadian Kodokan black belt association : You are currently on the Canadian Kodokan black belt association, now known as Judo Canada. Please take the time to browse the website and enjoy learning the many roles a judoka can explore in his journey and discover the many events in Canadian judo.

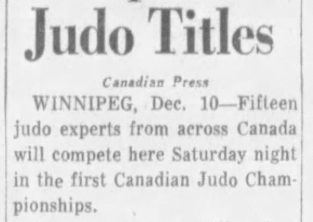

1959

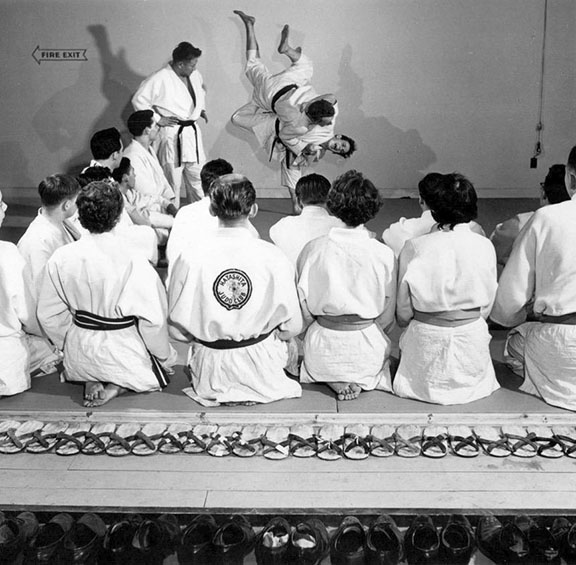

First all Canadian Judo Championships held in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Fred Matt of B.C. became the first national champion & Elaine McCrossan was the first women in Canada to be promoted to black belt .

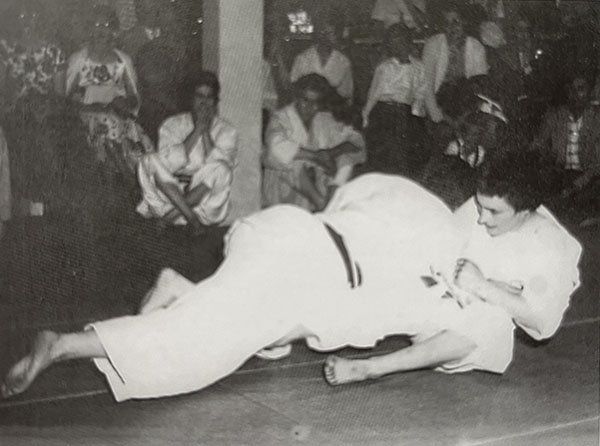

1st International competition for women at Hatashita Dojo.

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

« NO weight Classes !

Having won sole affiliation with the International Judo Federation, the CKBBA now set about organizing a country-wide championship in order to select possible entries into the World Judo Championships. The first such Canadian Championships were held in 1959 in Winnipeg. There were about 3,500 judokas in the country at the time, and of these, there were 188 black belts.

There were no weight classes in these first national championships. Everyone fought in the same division and only one champion was declared. »

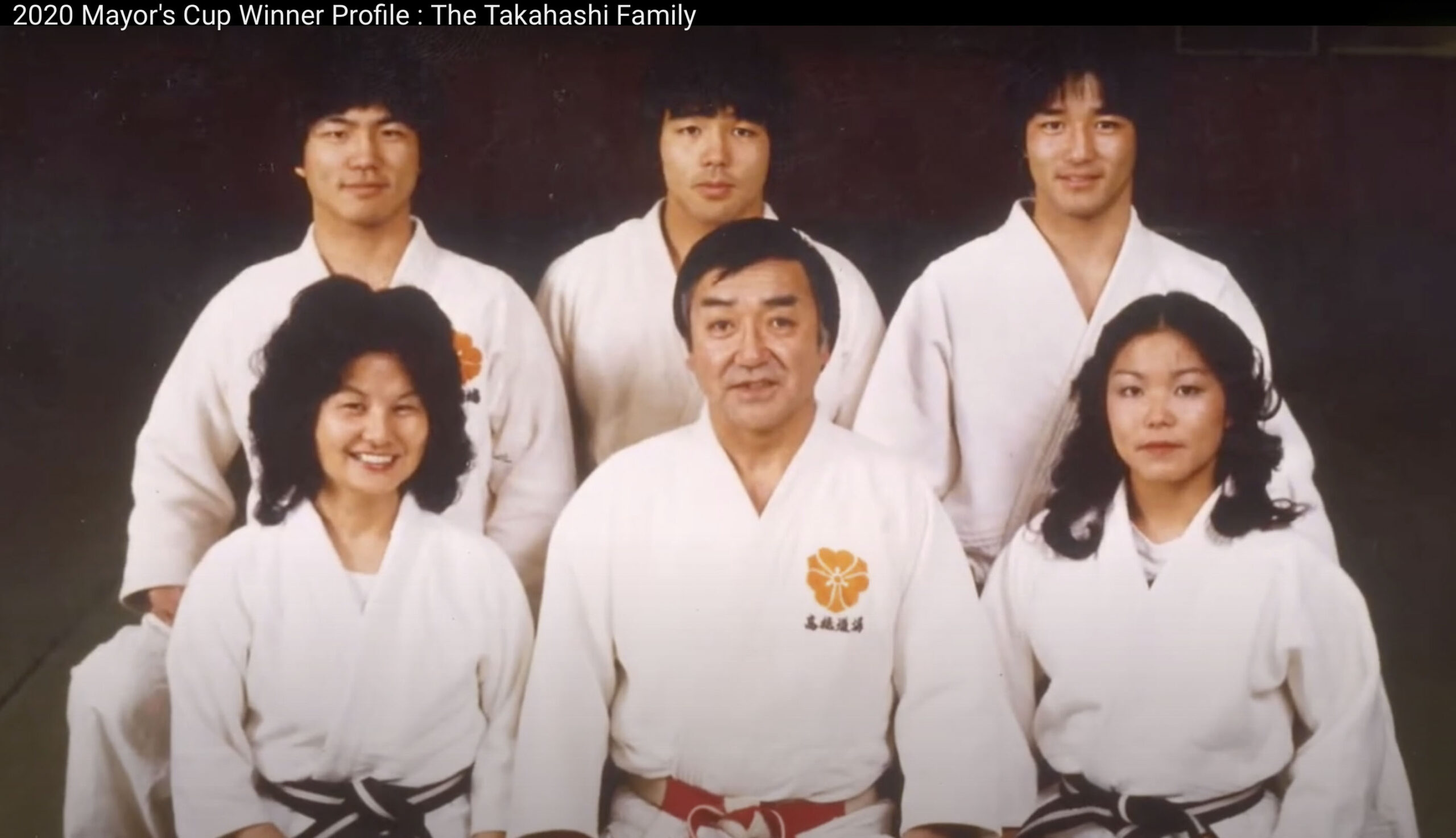

«The winner was Fred Matt (3rd Dan) from Vancouver. One of those Matt defeated in the preliminaries was Masao Takahashi, whose son Phil would later become one of the few Canadian judokas to win a world championship medal. As a true Canadian Champion, Matt represented Canada at the Pan-American Championships in Mexico that same year. There he won gold medals in both heavyweight and open divisions. »

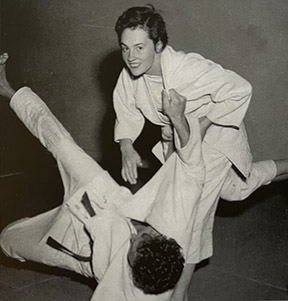

« Women in Judo

While the men were busy in the boardrooms and organizing their first national championships, oblivious to them, the women were quietly ma king their own history. The year 1959 was significant on two accounts – the very first international tournament for women was held at the Hatashita Dojo in Toronto, and Elaine McCrossan passed the Ontario Judo Association’s November black belt grading exam to become the first Canadian female to be promoted to 1st Dan. In Quebec, Céline Darveau, one of the first women to earn her black belt, also became the first Canadian female referee. »

« If there was one contribution to the sport of judo from the Western World, it was the early acceptance of women into the competitive aspect of the discipline. The first Women’s Canadian Judo Championships were held in Montreal in 1976: the first World Judo Championships for women were held at New York City in 1980: the first World University Championships for women were held at Strasbourg, France, in 1984: and after being a demonstration sport in the Seoul Games, women’s judo became a full-fledged Olympic event in the Games of the XXVth Olympiad in Barcelona, Spain.

Keiko Furuda (1913-2013) was well known throughout the world for her expertise in katas. She gave several clinics in Canada during the 1960 and 1970’s. She was the granddaughter of Hachinosuke Fukuda, one of the men who taught Jigoro Kano the art of jujitsu. All her life, she traveled the world and teach kata. Her last visit to Canada was in 1997. Fukuda-sensei was the highest-ranking female judoka in the world at 9th Dan. »

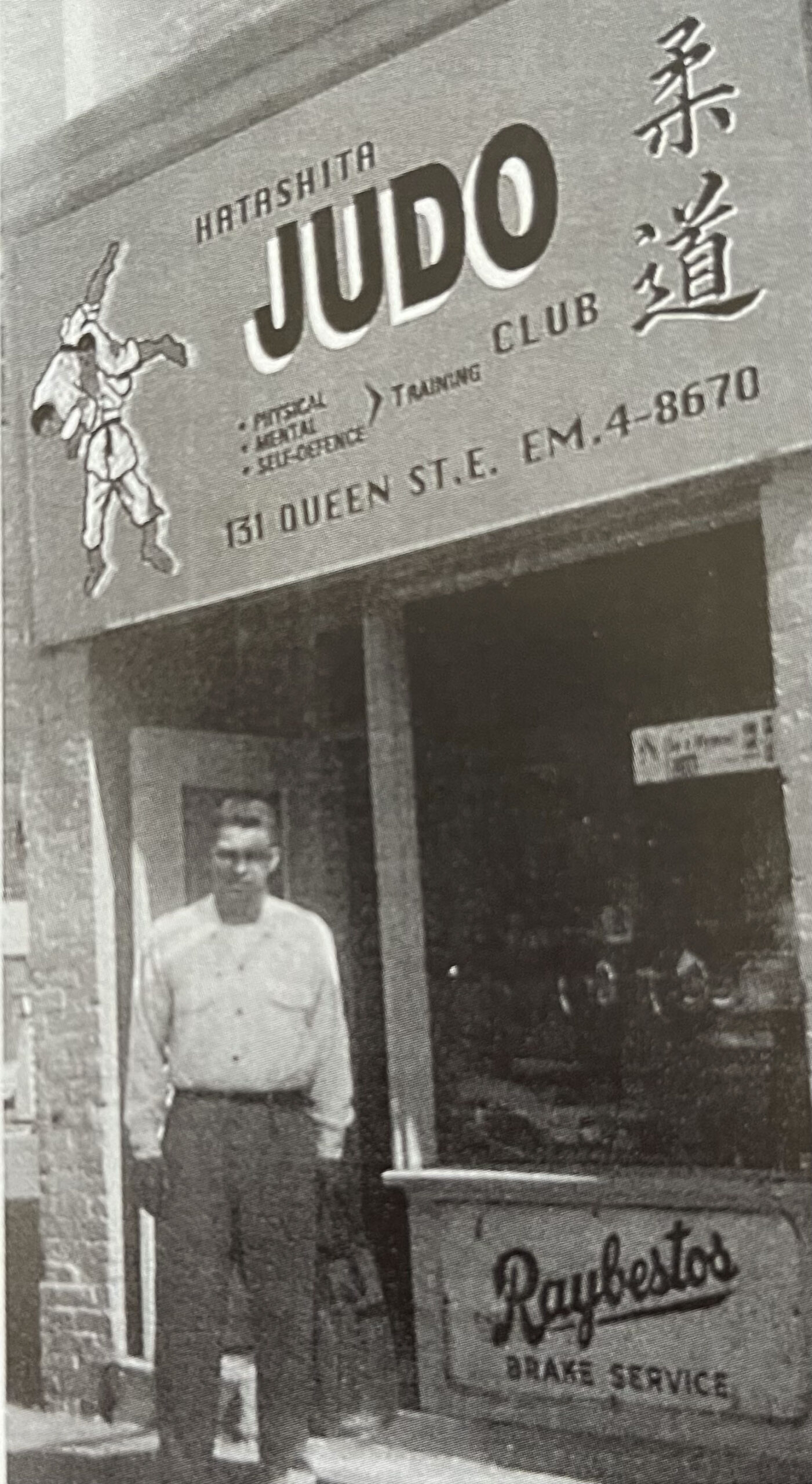

The Hatashita Dojo and it’s founder Frank Minoru Hatashita

Hatashita relocated to Toronto after the war and willingly put in the time under poor conditions, in humble surroundings, to establish his own dojo. Possessed of a strong will and spirit, Hatashita the sensei developed many top judokas in Canada. The Toronto Hatashita Dojo became famous in Eastern Canada and the Mid-Western States for its five-man judo teams during the 1950s and 1960s, winning title after title.

Most judo sensei were, and are, volunteers. Frank Hatashita saw some business potential in dojo ownership and turned his club operation into a full-time business. A precarious step at the time, but he ran it for 47 years. And from the Toronto bas Hatashita organized satellite dojos in other cities right across Ontario. In total he sponsored close to 100 satellite clubs.

Being his own boss, he could also devote time to the organization and development of judo not only in Canada, but throughout the world. A charismatic leader, he became known internationally as “Canada’s Mr. Judo.” In 1961 he succeeded Masatoshi Umetsu, becoming the third president of the CKBBA, and served in this capacity for the next 18 years. He also became President of the Pan-American Judo Union wich governs judo throughout the Americas serving four terms. As well, he was one of five vice-presidents of the International Judo Federation.

Little was known of the sport of judo outside of the Japanese Canadian communities before Frank Hatashita. He changed that. He brought judo to the people. He wrote articles for the newspapers. He published a monthly Canadian Judo News Bulletin. He put on countless demonstrations and clinics. And when the Canadian Olympic Association contemplated a 1964 Olympic team without a single judokas, Frank went on a publicity campaign to get Doug Rogers named to the team. Judo in Canada would not be where it is today without Frank Hatashita. Above anything else, Hatashita sensei loved to teach judo. Every day of the week.

While is decisions as president were not without some controversy, no one could question his dedication and lifetime of service to judo in Canada. Frank Minoru Hatashita was inducted into the Judo Hall of Fame in 1996 and was the first Canadian to be promoted to 8th Dan.

Frank Hatashita died in 1996, but his presence can still be felt all around America with the martial arts equipement company bearing his name. It is lead in the United Staes by his daughter, Lia, and in Canada by his nephew, Roman.

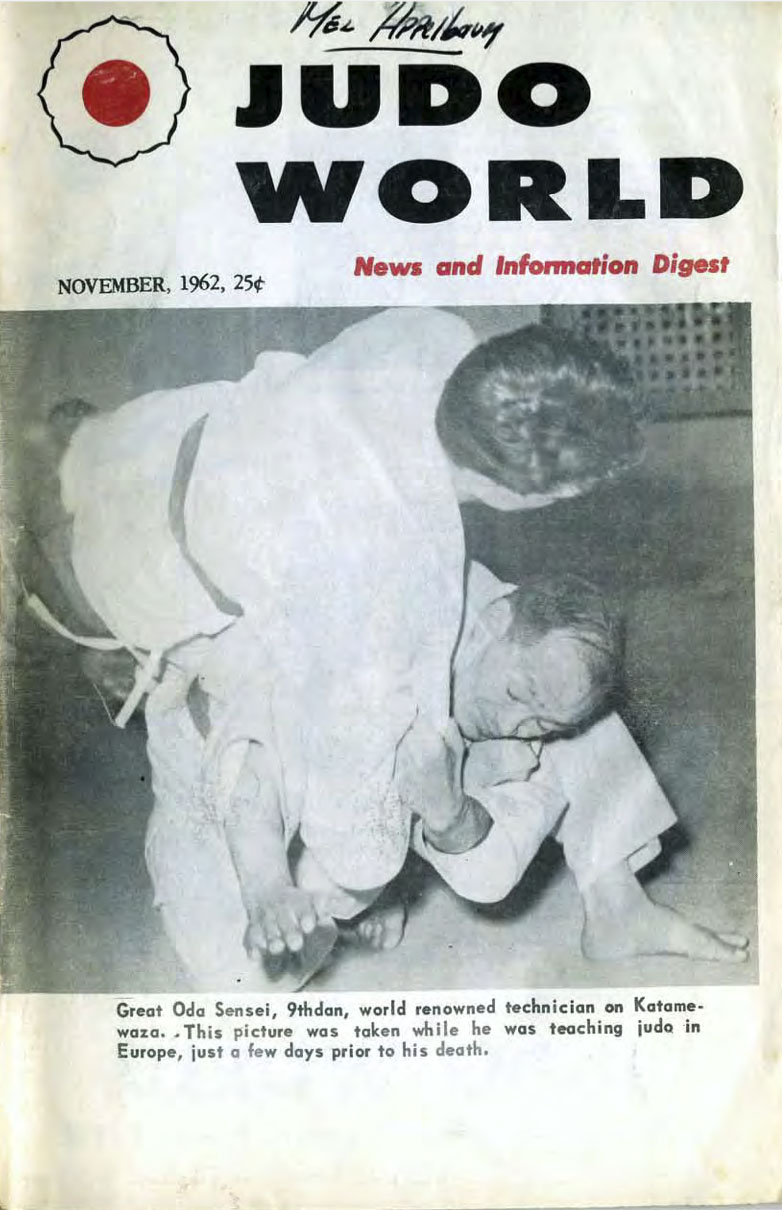

Frank Hatashita was a real entrepreneur and promoter of judo. In 1959 he established the Judo News Bulletin. The name changed to The Canadian Judo News in 1960, with photos appearing on the front cover in 1961. In July of that same year the name was changed to Judo World. The subscription rate was 3$ per year.

For more history :

Fred Matt

Céline Darveau

Hakudokan

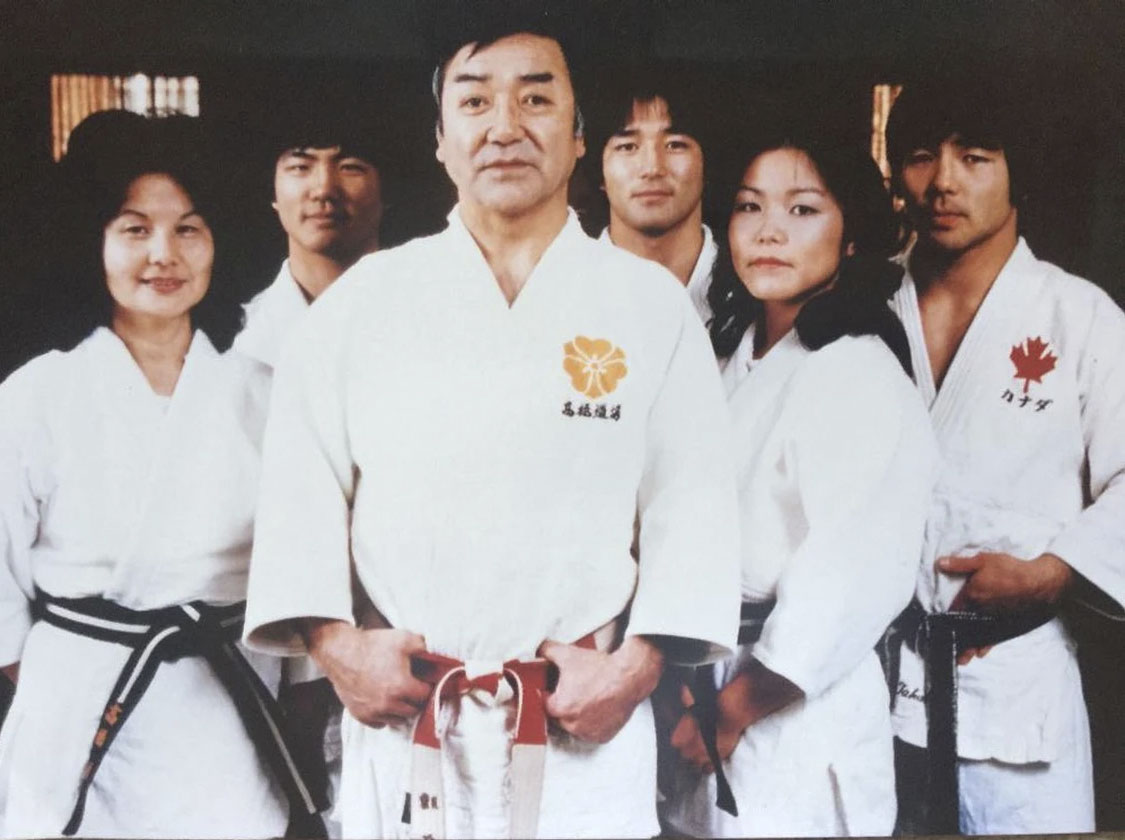

The Takahashi Family

Masao & Phil Takahashi

Phil Takahashi

Takahashi Dojo

Keiko Fukuda

Hachinosuke Fukuda

Frank Minoru Hatashita 1968

Judo World 1962

Masatoshi Umetsu

Pan-American Judo Union

Hatashita Judo Open

Peterborough Hatashita Judo Club

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1964 - 1965

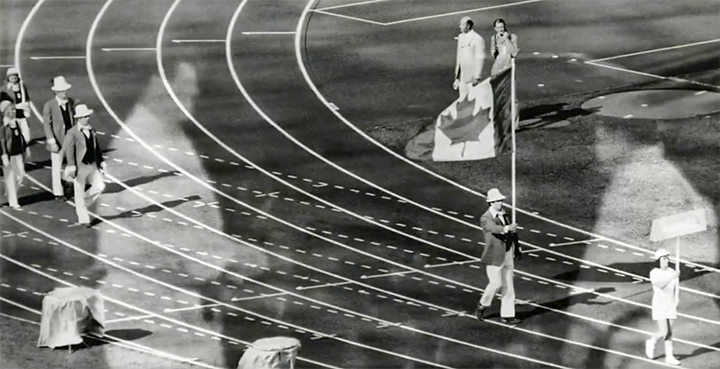

1964 – Judo joins the Olympic Games in Tokyo and Doug Rogers wins a silver medal and becomes Canada’s first Judo hero.

1965 – Doug Rogers wins the first medal (bronze) for Canada at World Championships

Excerpt from Canada’s Sports Hall of fame web site :

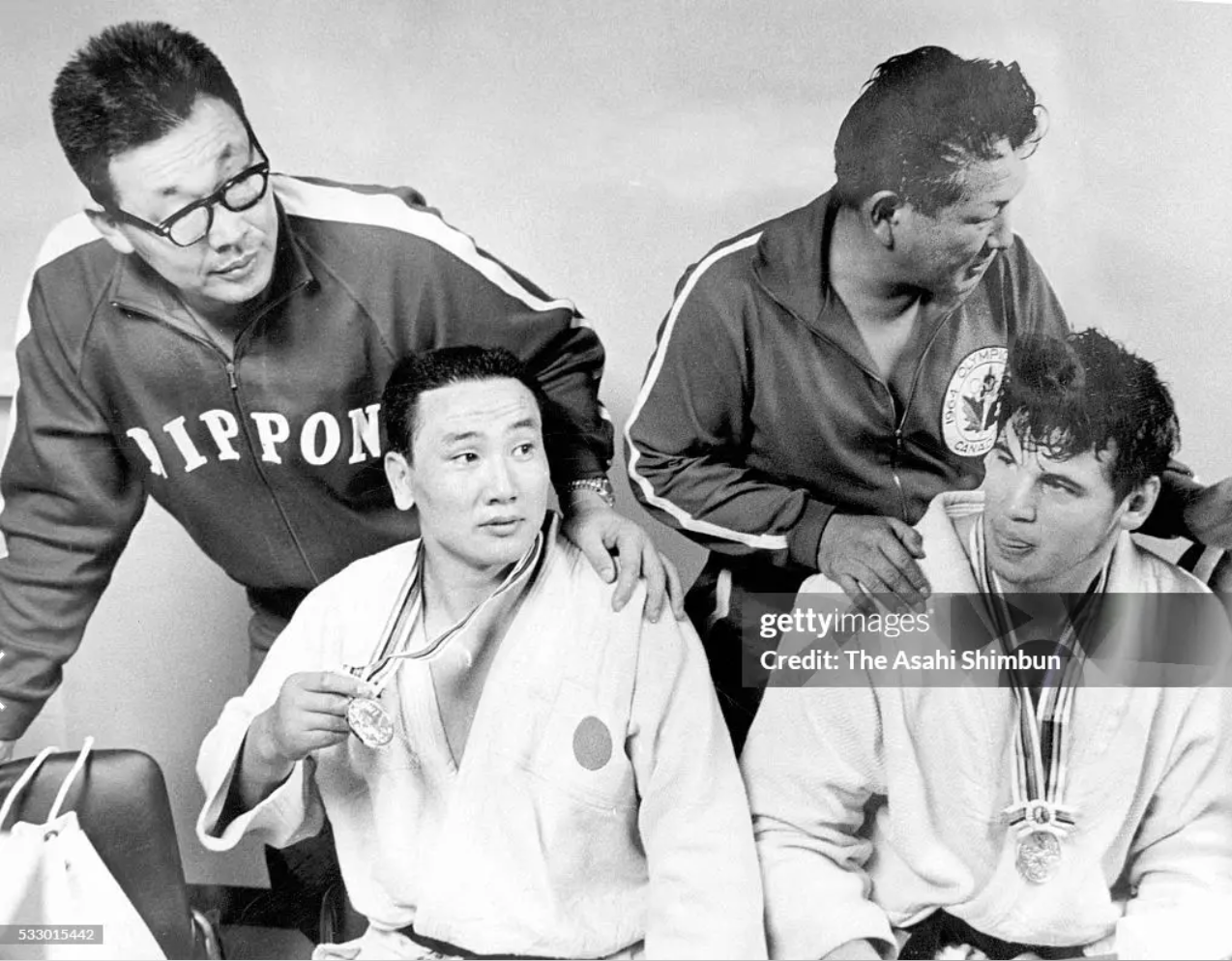

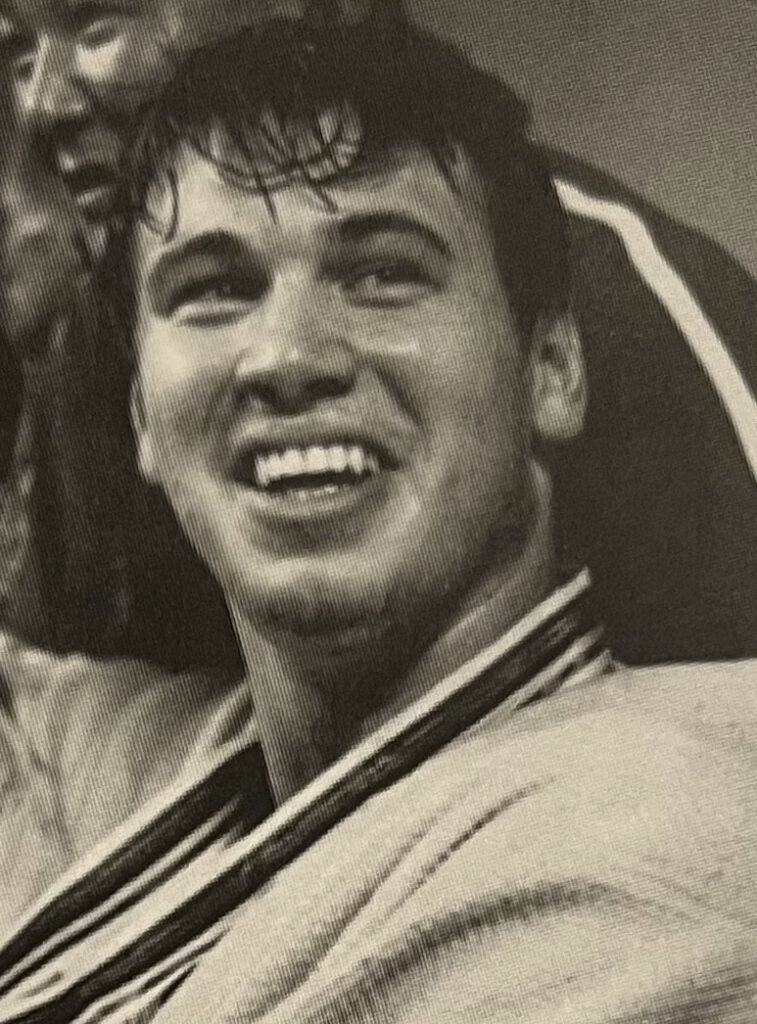

« After three-and-a-half years in Japan, Rogers had become an accomplished judoka and was selected to Canada’s 1964 Olympic team. Rogers was the dominant figure in Canadian judo in the mid-1960s, winning the national heavyweight championship four years running from 1964 to 1967.

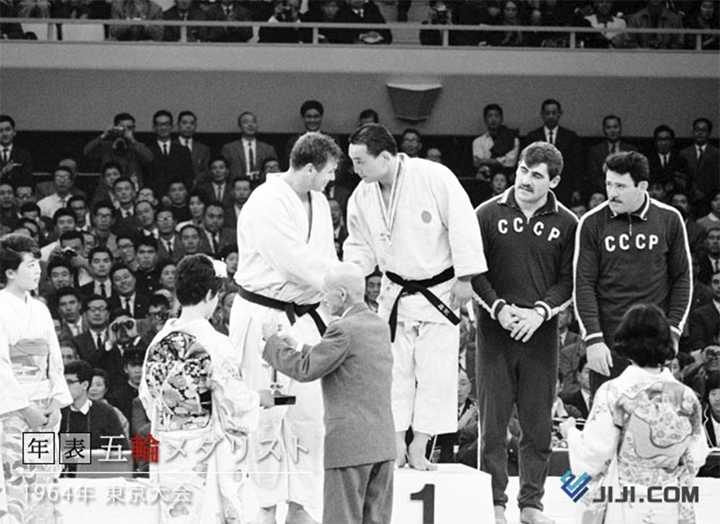

But it was back in Japan, at the 1964 Olympic Games, that he made his mark on the international scene. In the semi-finals of the heavyweight competition at Tokyo’s Budokan, Rogers won a clear decision over the competitor from the Soviet Union.

Only ten minutes later, however, he was back to face Japan’s famed champion Isao Inokuma. They had trained against one another at the Kodokan. Neither judoka was able to score a decisive victory and Inokuma was awarded a close decision, with Rogers settling for a silver medal. After the Olympics, Rogers remained in Japan to train full-time with sensei Kimura at Takushoku University. Despite his 1964 Olympic success, 1965 was perhaps the greatest year of Rogers’ competitive career. »

For more history :

Judoka

Video Collection of National Film Board

Hall of Famer

Doug Rogers

Inducted in 1977

Alfred Harold Douglas ROGERS

Mr. Rogers was inducted as an athlete into Judo Canada’s Hall of Fame in 1996

Isao Inokuma Olympic 1964

TOKYO, JAPAN – OCTOBER 22: Gold medalist Isao Inokuma (L) of Japan and silver medalist Doug Rogers (R) of Canada attend a press conference after the Judo Heavyweight gold medal match during the Tokyo Summer Olympic Games at the Nippon Budokan on October 22, 1964 in Tokyo, Japan. (Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images)

Isao Inokuma – Judo Info

Tokyo’s Budokan

Nippon Budokan

Sensei Masahiko Kimura

Takushoku University

Kodokan Judo Institute

Team Canada

1964 Olympic Judo

British Columbia Sports Hall of Fame

1968

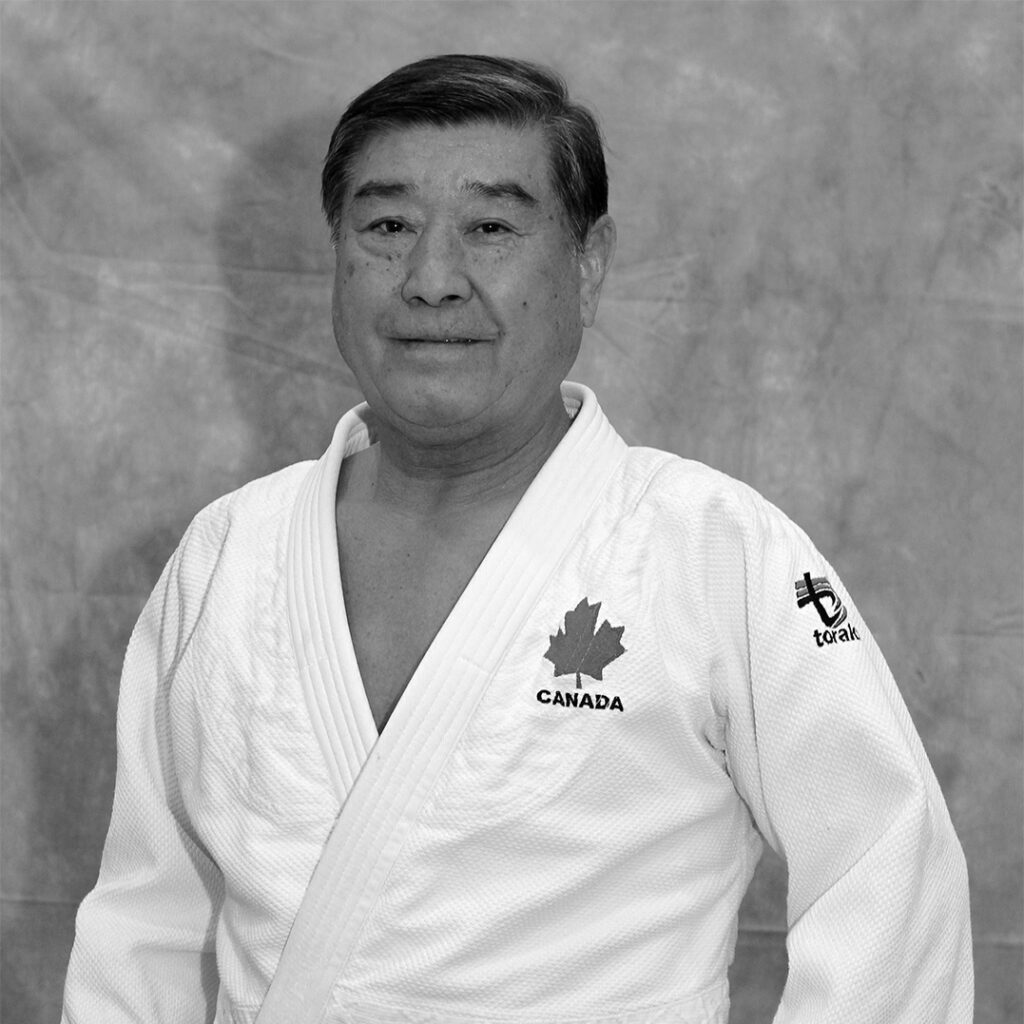

Hiroshi Nakamura arrives in Montreal from Japan, he became one of the most successful coach in the history of Judo In Canada and in 2019 is inducted by the COC Hall of fame

From the Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame Order of Sport :

An iconic mentor, trainer, and high performance coach who has devoted much of his life to developing judo in Canada, he continues to empower generations of athletes to fulfill their potential.

Hiroshi Nakamura has devoted much of his life to developing judo in Canada as an esteemed mentor, trainer, and high performance coach. Born in Tokyo in 1942, Hiroshi began practicing judo at the age of twelve, working with off-duty police officers at the Yanaka Police Dojo before attending the prestigious Kodokan Institute. One of only five Canadians to achieve the rank of Kudan (9th dan), Hiroshi ranked (by Black Belt Magazine) in the top 10 Japanese judokas (all categories) before injury cut his competitive career short. Becoming a dedicated trainer and coach, he began working with international athletes to prepare for the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo, the first year judo was included as a full Olympic sport. One of the judokas who trained with Hiroshi before reaching the podium that year was Canadian Doug Rogers, who claimed a Silver medal in the Olympic heavyweight division. Recognizing Hiroshi’s exceptional devotion, Rogers seized the moment and asked him to travel across the Pacific to establish a national training program that would give Canadian judokas unprecedented access to competitive training in their own country.

When Hiroshi moved to Canada in 1968, he committed to a bold vision of making judo as popular as ice hockey across the Great White North. Settling in Québec, where the sport had few practitioners, Hiroshi began offering lessons at Vanier College in Montréal while giving free demonstrations in the cafeteria at lunchtime to spark student interest. In 1973 he opened his own dojo, the Shidokan Judo Club, in Montréal. Under Hiroshi’s guidance the Shidokan became the most successful competitive judo program in Canada and remained home to the National Training Centre until 2014.

Securing his legacy as the most important individual contributor to Canada’s presence in international judo, Hiroshi coached Canadian judokas at 13 International Judo Federation World Championships between 1969 and 2007 and served as coach of the Canadian judo team at five Olympic Games between 1976 and 2004. Many of his protégés have also become vital leaders in the sport, including CEO and High Performance Director of Judo Canada, Nicolas Gill.

An insightful, compassionate mentor, Sensei Nakamura has helped generations of athletes at all skill levels cultivate values that transcend sport, building a foundation for success on and off the judo mats. Emphasizing self-discipline, humility, and perseverance, he patiently encouraged each judoka to fulfil their own unique potential, empowering them to aim high and focus on kaizen, or continuous improvement. Deeply committed to students in his care, before funding was available for the national training program, Hiroshi regularly opened his home to young athletes who would move across Canada to work with him. Continuing to train future Olympians at the Shidokan today, Hiroshi has also used his expertise to help others by teaching women’s self-defence classes, offering judo programs for at-risk youth, and supporting young judokas in need of financial assistance through the Nakamura Gill Foundation.

For more history :

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame Order of Sport

CBC

Team Canada

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame

Sensei Hiroshi Nakamura Induction Speech

Coach, 2013 Geoff Gowan Award Winner

Judo Canada video demonstration series by sensei Hiroshi Nakamura

Kodokan Judo Institute

Vanier College

Sportcom

Shidokan Dojo

National Training Centre

Black Belt Magazine

Judo Canada Team Training 1975 Part 1

Judo Canada Team Training 1975 Part 2

1972

In Munich, Raymond Damblant became the first Canadian to referee at the Olympic Games.

From the Panthéon des sports du Québec website:

“French of origin, born in January 1931, Raymond Damblant is a physical educator, state certified in combat sport, who has practiced judo on four continents and taught this sport on three of them.

He was a member of the French team during three international meetings in Sweden, England and Spain before heading to Yugoslavia to join a team of teachers and develop judo in that country.

Despite a serious training program, I competed in three French championships without earning a title, not even any consolation! However, I reached the quarterfinals twice and the semi-final once,” underlines Raymond Damblant. On the other hand, at a time when weight categories did not exist, he won the national spring cup, a competition open to everyone except national medalists, and a good fifteen various meetings.

In 1959, Raymond Damblant received an offer and opted to come to Canada. He himself describes his departure for Canada as a risky adventure, since he had neither firm contract nor guarantee. He won the provincial championship and finished third at the Canadian championship.

It is not his exploits as an athlete that allowed him to enter the Quebec Sports Hall of Fame, but rather his involvement and the determining role played in the development of judo here.

Ninth dan in judo, as technical director of the Hakudokan judo club, he has trained more than 210 black belts on three continents.

Raymond Damblant was the founding president of Judo Québec in 1966, a position he held until 1971 before becoming the technical director of the organization until 1975. Responsible for combat sports at Expo 67, he acted as director of competitions during the Olympic Games in Montreal in 1976 and played the same role during the Olympic Games in Los Angeles in 1984.

In 1967, he became the first Canadian to receive the title of international referee at level A, which led him to referee at five world championships, nine Pan American Games and be selected as referee for two Olympic Games, those from Munich in 1972 and from Moscow in 1980.

He was also involved in Judo Canada, first assuming the vice-president from 1963 to 1970, the presidency of the grades committee from 1972 to 1989 and that of the technical committee from 1982 to 1986. Subsequently, he became general secretary of the organization from 1987 to 1996 before being named a life member in 2000.

Raymond Damblant adds to his already busy career the technical direction during three Canada Games in 1982, 1986 and 1990 and can be delighted to have played the role of chef de mission for Judo at the Olympic Games in Seoul and Barcelona and at four World Championships and two Pan American Games.”

For more history :

Panthéon des sports du Québec

Quebec Sports Hall of Fame

Hakudokan

IJF

37e Gala Sports Québec 2009

37th Gala Sports Quebec 2009

NFB

Judo Québec

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 1

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 2

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 3

Interview with Raymond Damblant, part 4

Martialement vôtre

RDS broadcast

RDS broadcast showing Judo

1976

Montreal Olympics Games & the first edition of a women national championships

Excerpt from the Canadian encyclopedia :

On 17 July 1976, at 3:00 p.m. more than 73,000 people gathered in the Olympic Stadium to take part in the Opening Ceremonies of the Montréal Olympics. The rituals began with the arrival of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, accompanied by Prince Philip and Prince Andrew and by IOC president Lord Killanen and Commissioner of the Games Roger Rousseau.

This was followed by the procession of athletes into the stadium. After the Queen officially opened the Games, the Olympic flame was carried into the stadium by two 15-year-old athletes, Sandra Henderson from Toronto and Stéphane Préfontaine from Montréal, to the sounds of the Olympic Cantata written by Louis Chantigny.

Excerpt from JOURNAL YUDANSHA of December 2006 :

It has been 30 years since women first competed at the Canadian National Championships. At the 2006 Senior and Juvenile/Junior Canadian Championships, it was time to reflect and honor our past. There we recognized the contribution of so many over the past 30 years and considered what the future might hold. Canadian females have gone from participating at small regional judo club tournaments to, not only participating in the past 30 Canadian Championships, but also at many international tournaments around the world, including the Olympics since 1988.

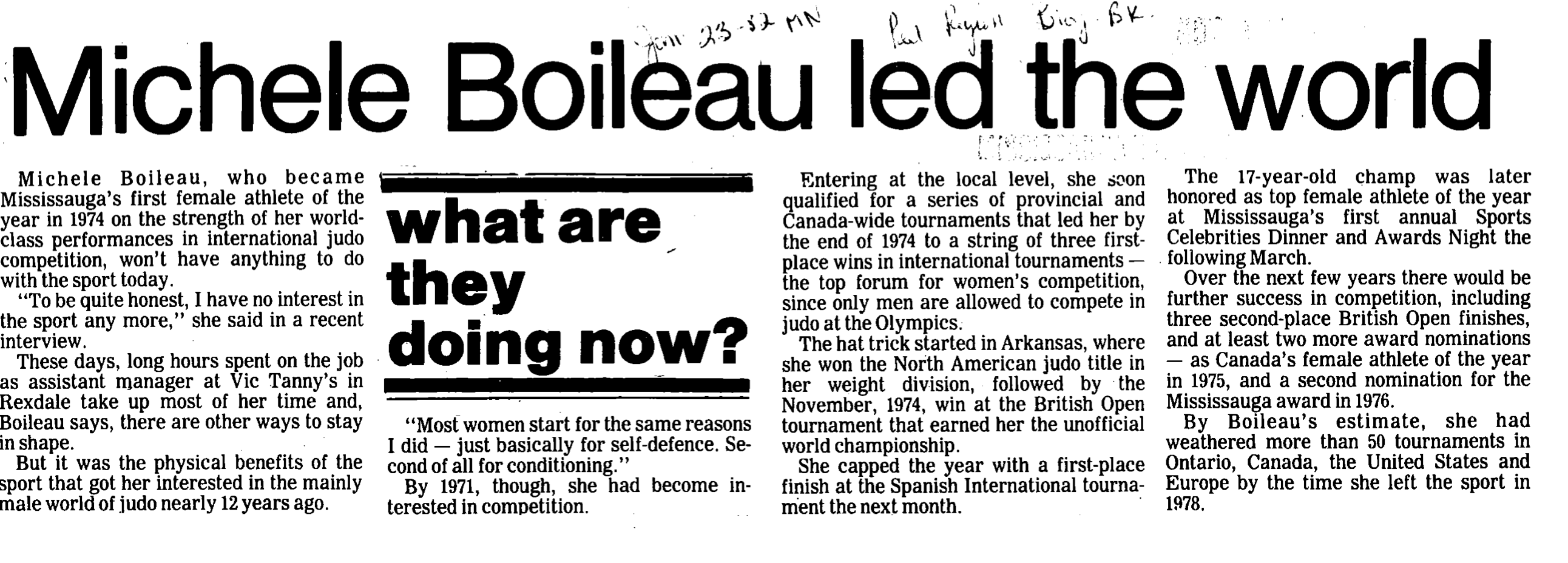

In Lethbridge, AB, during the opening ceremonies of the Juvenile and Junior Nationals, Judo Canada honored all of the original 1976 National women’s champions, Monette Leblanc, Diane Hardy, Sue Gribben, Lorraine Methot, Yvonne Lestrange, Michelle Boileau and Tina Takahashi by presenting each of them a beautiful, framed certificate by Judo Canada.

The Yudansha newspaper: Former Judo Canada newspaper which appeared 2-3 times a year, from 1983 to 2007.

For more history :

1976 Olympic Games – 40 years

Surreté du Québec’ heritage

Olympics COJO Report 1976

Montreal 1976 Summer Olympics

The Canadian Encyclopedia

The Olympic Games open in Montreal – July 17, 1976

Parc Jean-Drapeau

Archives Montreal

Pierre De Coubertin

Jean Drapeau

IJF

L’esprit du Judo

Olympedia

The best of Judo Olympic Games 1976

Judo 1976 Montreal: Coage (USA) – Felipa (AHO) [+93kg]

The best of Judo Olympic Games 1976

1976 Olympic Judo Team

Brad Farrow

Wayne Erdman

Rainer Fisher

Joe Meli

Tom Greenway

Coach Hiroshi Nakamura

Referee Jim Kojima

First edition of a women national championships

Results

Monette Leblanc

Diane Hardy

Sue Gribben

Lorraine Méthot

Yvonne Lestrange

Michelle Boileau

Tina Takahashi

1977

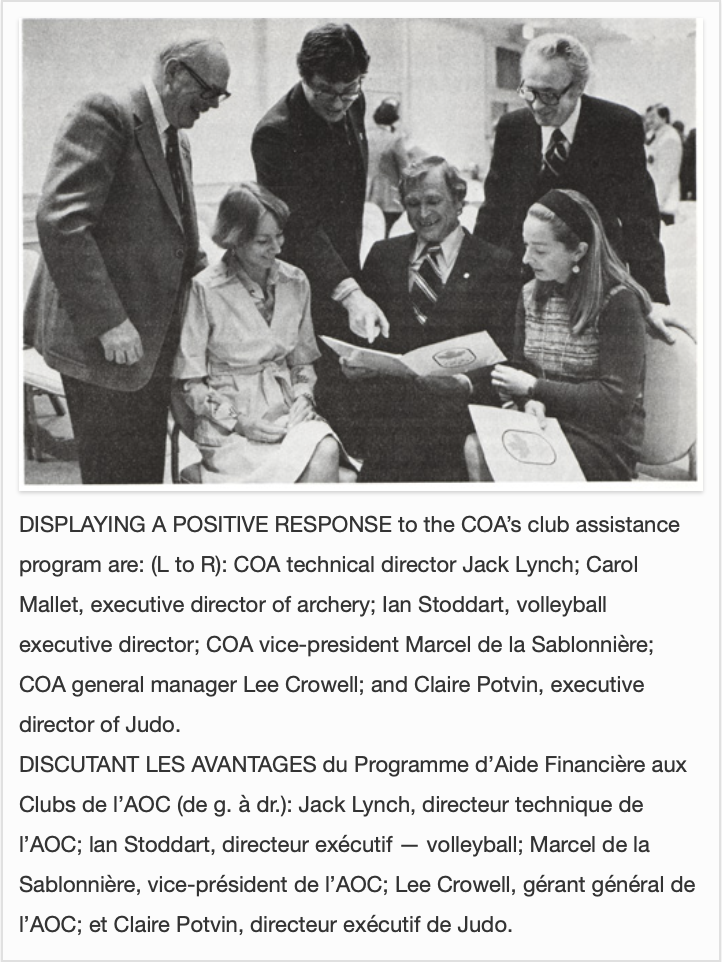

CKBBA also known as ‘’Judo Canada’’ opens an office in Vanier, On Claire Potvin serves as the 1st Executive Director.

Excerpt from Canadian Sports History website :

Van De Walle came to Canada to put in a month’s work, arriving in mid-December 1980. He was invited here to conduct training clinics — in Vancouver, Lethbridge, Toronto, Peterborough, Ottawa, Trois-Rivières, Montréal, Halifax, and St. John’s — for judokas who aspire to be Olympic champions.

Potvin says the reason for bringing the gold medallist to Canada was more than just to set up an exchange of ideas.

“Lately we’ve been trying to get outside sources into Canada for clinics to show our boys how other athletes train,” she says. “Our judokas usually see their rivals only in a very tense competitive atmosphere. This type of clinic not only brings them face-to-face in a relaxed atmosphere with one of the world’s best. It will also perhaps enable them to better handle the competitive tension.”

The impression that Van De Walle left, however, was hardly one of relaxation.

During the Ottawa clinic, for example, he had finished a scheduled class and offered to stay longer if any of the participants wanted more randori (free practice). He proceeded to put those who stayed behind through a very gruelling workout. Potvin was on hand for the session and heard Phil Takahashi, one of Canada’s top judokas, finally tell Van De Walle that he was tired.

“You’re not tired,” rejoined Van De Walle. “When you want something badly enough, there’s no such thing as being ‘tired’.”

Potvin says the Canadian judokas who participated in the Van De Walle clinics all agreed that they had seldom enjoyed such a profitable workout.

“It’s fine to bring in guest coaches or have our athletes taught by someone who was on the international judo circuit 10 or 15 years ago,” she says. “But they also learn from a guy like Robert who is getting top international results right now.”

For more history :

Canadian Sport History

Champion Magazine

May 1978

Claire Potvin

Canadian Sport History

Champion Magazine

March 1979

Claire Potvin

Canadian Sport History

Champion Magazine

May 1978

Claire Potvin

Canadian Sport History

Champion Magazine

May 1981

Robert Van de Walle

1980 Moscow Olympic Judo Team Canada

Vanier, Ontario

1977 Office in Vanier

1980

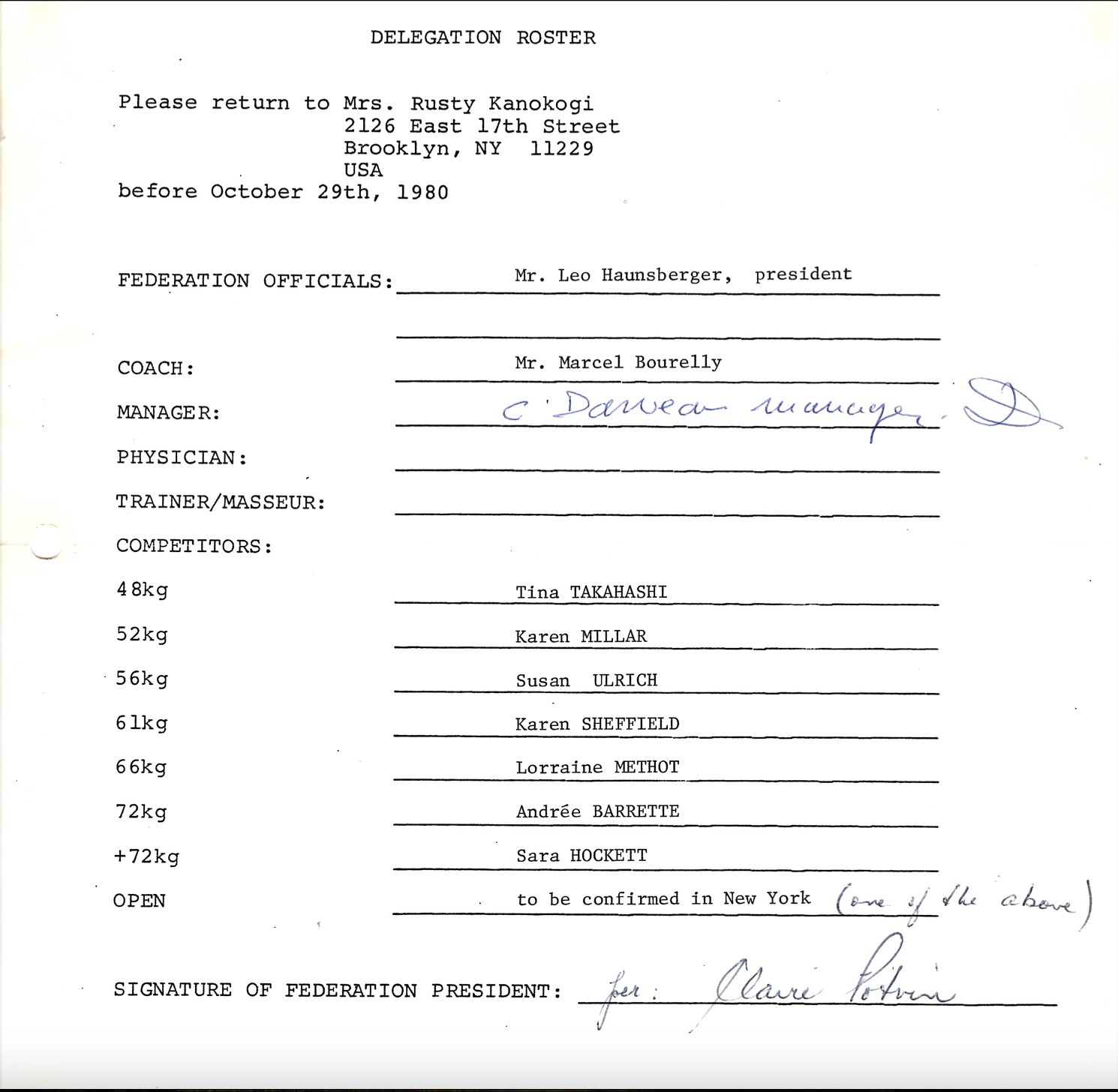

1st female World Championships in New York, Tina Takahashi places fifth in the under 48 kg category.

Excerpt from the IJF website Women’s Judo : The Pioneers (2) :

«Following Rusty Kanokogi’s example and due to the expansion of women’s judo, the European Judo Union organized a first experimental competition in 1974, in Genoa, Italy. The following year, in Munich, Germany, the first Women’s European Championships were held. A similar evolution happened around the world. The first Oceania Women’s Championships were held in 1974 and in 1976 Pan-America followed and in 1978, Japan.

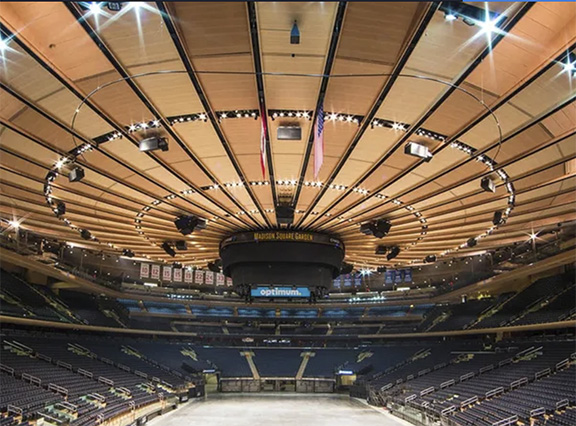

Time had come for women’s judo to become global. In 1980, Kanokogi organized the first women’s judo world championship in Madison Square Garden, sponsoring it through the mortgage of her own home. She was also the driving force behind the introduction of women’s judo at the 1988 Summer Olympics and in Seoul she was coach of the first United States Olympic Women’s Judo Team. She would coach her personal student, Margaret Castro, to a medal at these Olympic Games. Women’s judo was fully integrated into the Olympic program in 1992, in Barcelona, Spain.»

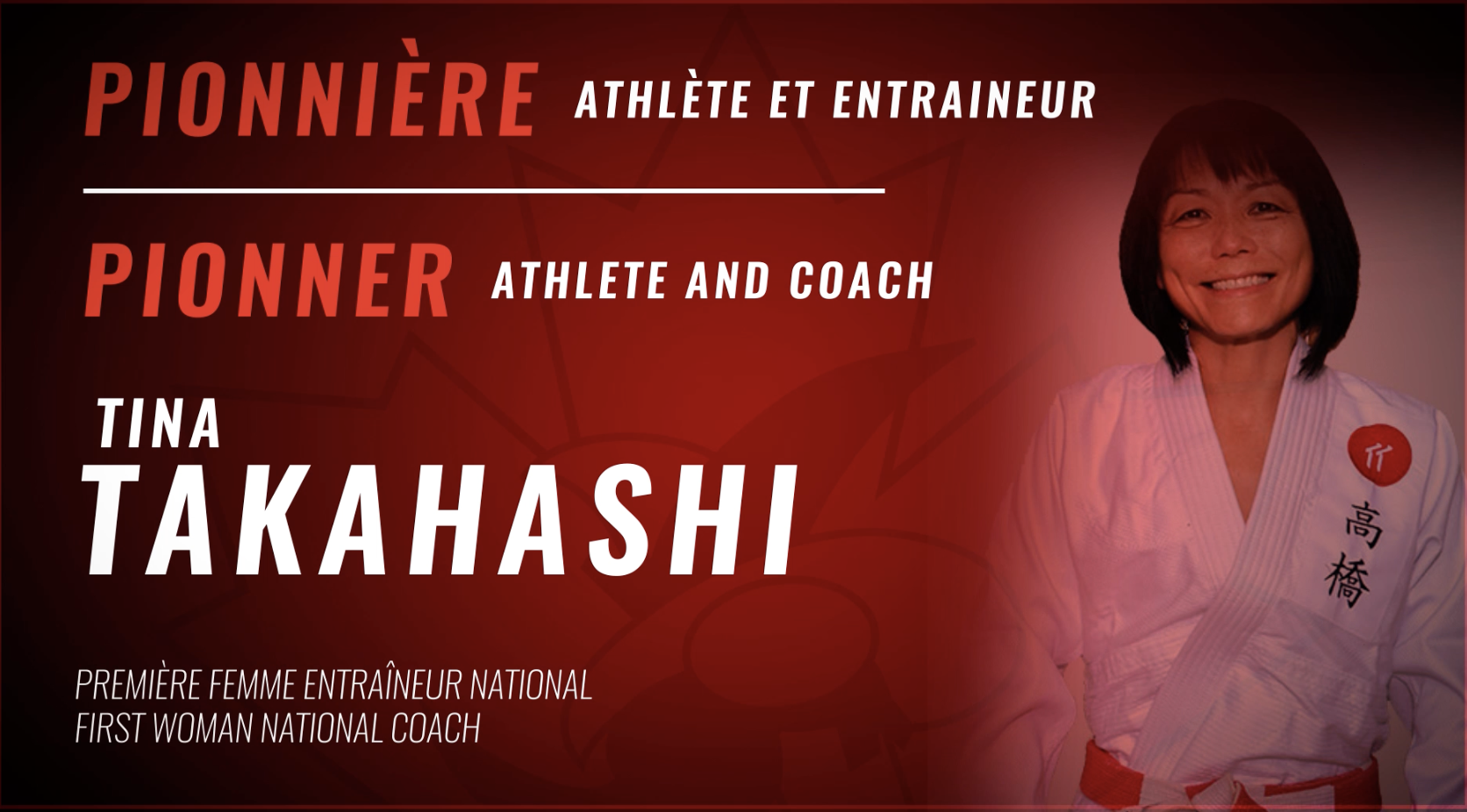

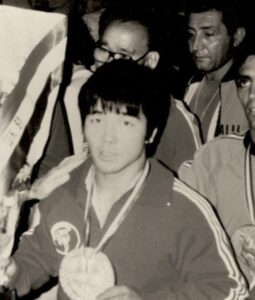

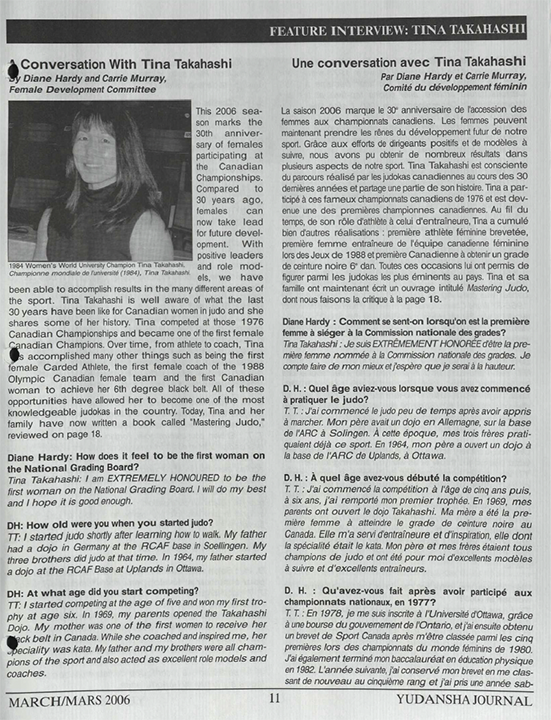

Tina Takahashi

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

« Tina was the first Canadian female to win a World University Championship gold medal (1984) ; she competed in the first World Judo Championships for females in New York (1980) ; she was the first female judoka carded by Sport Canada (1980) ; she was the first female to coach a Canadian women’s national team and Olympic Team (1988) ; she competed in the first Canadian Championship for females (Montreal, 1976). »

For more history :

JUDO , No. 6 January 1981

IJF

IJF 1980 Memorabilia

IJF 1st Women’s World Championships 1980

All participating athletes

Rusty Kanokogi Story

Madison Square Garden

New York, USA

Rusty Kanogi

All participating Nations

Tina Takahashi Pioneer

Tina Takahashi

Tina Takahashi martial art school

Karen Millar

Susan Ulrich

Karen Sheffield

Lorraine Méthot

Andrée Barrette

Sara Hockett

Céline Darveau (Manager)

Marcel Bourelly (Coach)

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1981

Phil Takahashi and Kevin Doherty win bronze medals at the World Championships

Except from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada :

« As a “natural” 60 kg fighter, Phil only had to sweat off a kilogram or so to make weight. Then he was ready with his best moves – a shoulder throw, a shoulder wheel, and a body crop, in dozen years of being the top man in the country in his division, Phil competed in well over 100 tournaments, domestic and international, and won more than his share of them. The high point was his bronze medal in the 1981 World Judo Championships.

In this tournament, held in Maastricht, Holland, Phil lost only one of five matches, and that to the eventual silver medallist. In the second round of matches Phil was pitted against a British judoka and scored a full point with a strangulation hold. It was a tough match though, and no sooner had he stepped from the mat, or it seemed, then he was summoned to fight the Czech.

The Czech fighter had an unusual style. He would not grip the ‘gi’ in the unusual fashion, but instead attacked the legs. All perfectly legal, but unconventional, and it took away Phil’s best moves. He lost his only match, and it put him out of contention for the gold medal. In the match for third place, Phil defeated the French entry and carried home a bronze medal for his efforts. »

« Kevin’s father, William (Bill) Doherty, joined Atsumu Kamino’s Kidokwan dojo in Toronto upon emigrating from Ireland, and that began a love affair with the sport that spread to Kevin and his brother. Naturally, Doherty, the elder, became Kevin’s instructor. And he made Kevin work at it – although he needed little persuading. When Kevin was 17, his father thought Kevin should go to Montral to polish his skills with Nakamura-sensei, so the young boy left home to live in another city as a carded athlete and part-time student.

As a 71 kg judoka, Kevin won his first Canadian title. Moving up to 78 kg in 1981, he competed in the World Championships, finishing third. His career was developing nicely. He was confident and strong – one of the few members of the National Team at that time who lifted weights. Some of the other team members felt that weight training had a negative effect on one’s speed, but Kevin could bench press 400 pounds, and never noticed any diminution in quickness. Kevin knew that at a certain levels of international competition strength was a necessity, but never a substitute for well-polished technique and he always trained in the dojo with great diligence. »

For more history :

World Championship 1981

Kevin Doherty

Phil Takahashi

Canadians that participated

Andrzej Sadej

Mark Berger

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

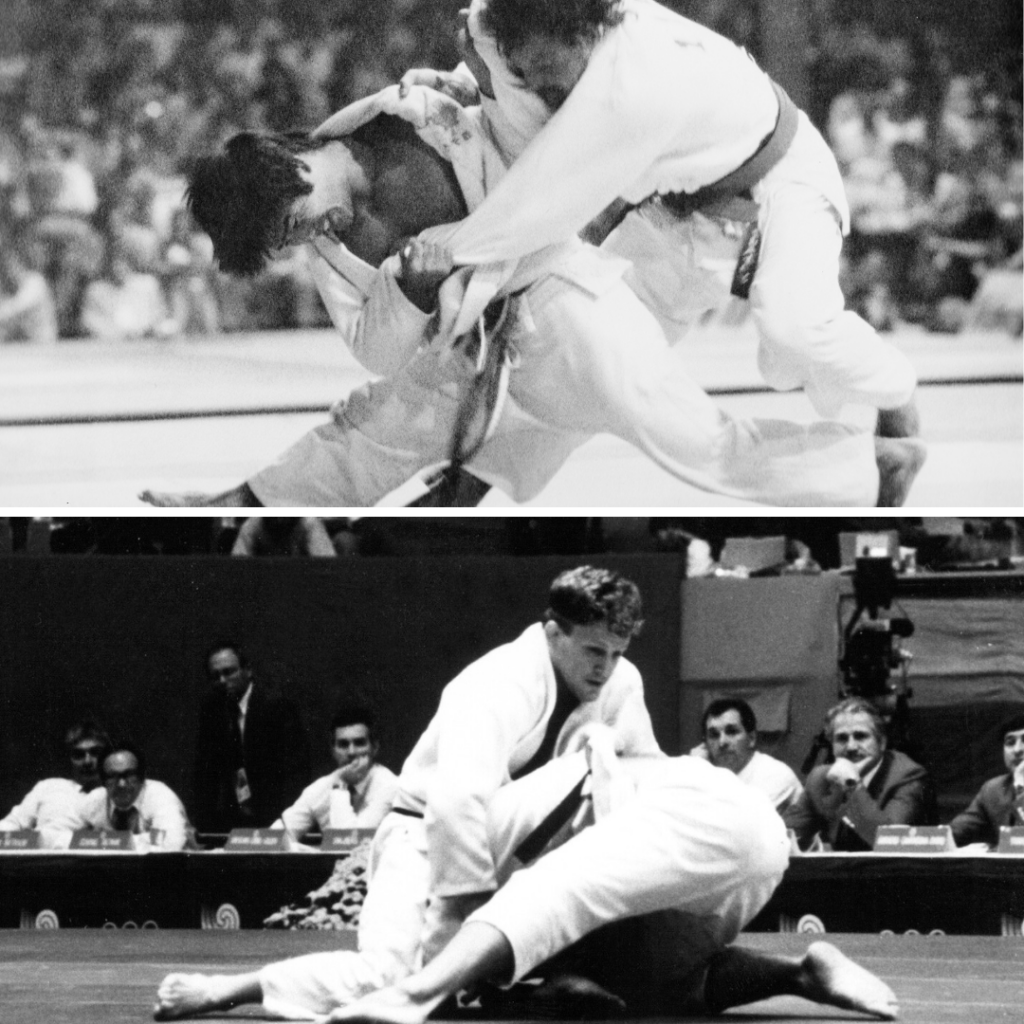

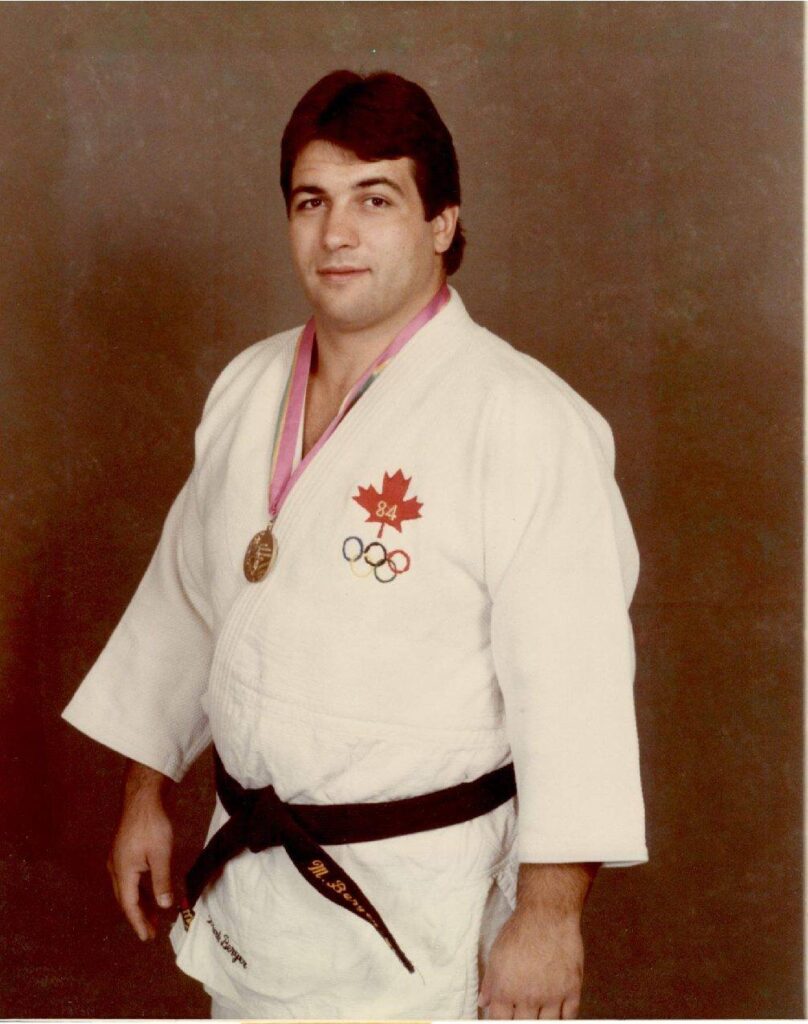

1984

Mark Berger wins a bronze medal at the Los Angeles Olympics & Tina Takahashi wins a gold medal at the World University Championships in Korea.

Except from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada :

« He actually met the standard earlier but could not be carded because he was not yet a Canadian citizen. He had emigrated from the Ukraine in the former Soviet Union. An accomplished athlete, he was a master of sport in wrestling, sambo, and judo even at that rather tender age.

The government had placed his family in Winnipeg because it held most promise for work for his tailor father. Mark, in this new country, despite the problems of language, found a job and joined the University of Manitoba Judo Club. It wasn’t long before he enrolled at the university in physical education. When he graduated, he became a high school teacher. On the way to his career goal, he proved to be one of the best judoka Canada ever had, and one of the best in the world.

In 1981, he won the Maccabiah Games in the heavyweight judo competition, as well as the Canadian title. This was a launching pad to the Olympics.

Being a heavyweight as well as an outstanding international performer made for some problems in Canada. Chief among them was a lack of sparring partners. Berger had to be especially careful not to injure any of his few larger teammates otherwise he would find himself alone on the tatami. The solution was to go to Europe or Japan to train.

To make ends meet, Mark, by now a father of two girls (both currently practicing judo) worked as a supply teacher and a bouncer in a nightclub and still managed to spend several weeks each year in Europe. There he could not only find an abundance of workout partners but could adapt to the “rougher” or more physical style of European judo. As Mark puts it, “In Europe, when you locked with your partner, you could feel the cotton stretch.“ It was a very powerful judo which could upset anyone not prepared for it. He also trained in Japan, where the emphasis was on smooth technique. He now had the two influences most current on the international scene, but it was not without some sacrifice. As Mark put it, “It wasn’t easy for me, but it wasn’t easy for anyone else, either.” He also noted that he was well treated in these foreign training camps because the opposition were interested in scouting him and seeing what he could do.

The high point of Mark’s career was winning a bronze medal at the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, the first Olympic medal since Doug Rogers accomplished the feat 20 years earlier in Tokyo. At the Games, Mark lost his first match to Saito of Japan, then proceeded to defeat three opponents to win the bronze medal for Canada. Mark decided not to continue his hectic pace after 1984 and did not return to the tatami until 1986. It was then that he won his fifth Canadian title. He was inducted into the Judo Canada Hall of Fame in 1996.

For more history :

1984 Olympics

The 1984 Olympic team

Glenn Beauchamp

Phil Takahashi

Kevin Doherty

Louis Jani

Fred Blaney

Joe Meli

Brad Farrow

Mark Berger

Coach : Jim Kojima

Tina Takahashi

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1988

Eddy & Pier Morten win bronze medals at the Paralympic Games in Seoul, South Korea to become the first ever Paralympic medalist in Judo for Canada & Female judo is present in Seoul Olympic Games as a demonstration sport, Sandra Greaves is the first Canadian women to participate.

Except from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada :

« In 1985 Sandra packed her judogi again, this time heading back east, and ending up on Bill Doherty’s doorstep in Ajax, Ont. Bill found her a job with the Provincial Ministry of Transportation. Sandra was able to train once more under her very first sensei. In that same year she won the national title in the 66 kg class. Convinced that her talents and dedication could take her further, Doherty-sensei talked Sandra into quitting her job and moving to Montréal to be trained by Hiroshi Nakamura.

The training was good, and the news that women’s judo would be added to the Seoul Olympics for the first time gave Sandra a dream – to become an Olympic gold medallist. As a demonstration sport, only the top eight in the world plus continental champions would be invited. Sandra would have to win the 1987 Pan-Am Games to be selected. At the Games at Indianapolis, she fought her way to the final. Standing in the way of her Olympic dream was Christine Pennick from the USA, who had beaten Sandra in their previous three meetings. Pouring her heart into the match, Sandra won by a koka, and with the win, a gold medal and a trip to Seoul, Korea. »

For more history :

Pier Morten

Eddy Morten

Sandra Greaves

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

1992

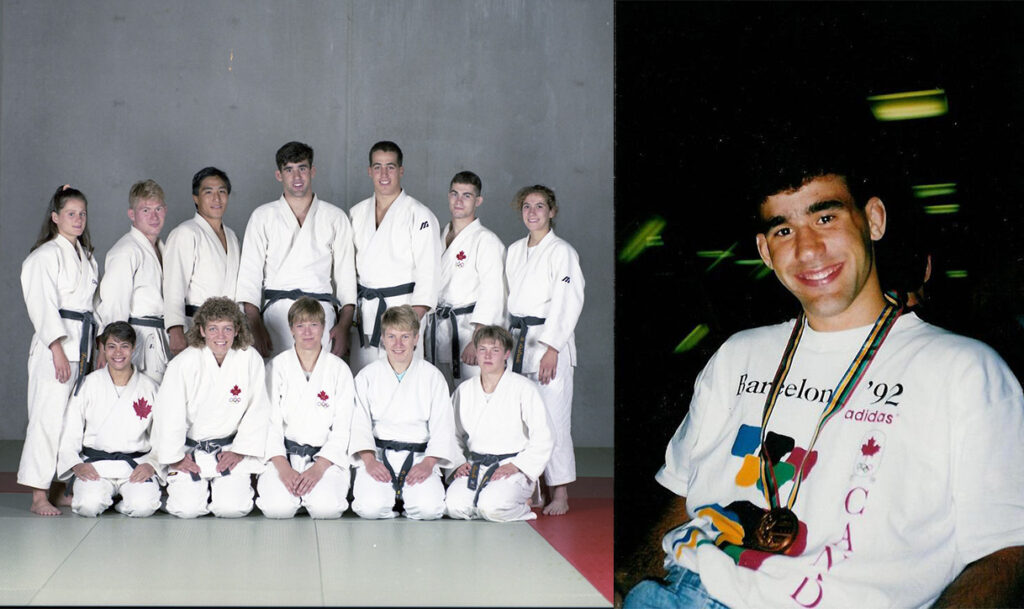

Women judo joins the Olympic program in Barcelona and a young Nicolas Gill wins his first Olympic medals.

Excerpt from the Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame:

« Gill’s first taste of national competition came during the 1987 Canada Games in Cape Breton. It was through this experience that Gill could test his mettle against the country’s best to develop his strategy and rise to the top. Gill captured the Gold medal in the 54kg category and continued on to take the Judo world by storm. Nicolas has competed at 4 consecutive Olympic Games (1992, 1996, 2000, 2004), winning the 86 kilogram Bronze medal at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games and the 100 kilogram Silver medal at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. Nicolas’ additional international success includes a Silver medal at the World Championships in 1993 as well as a Bronze medal in 1995 and in 1999; Pan American Games Gold in 1995 and again in 1999; a Commonwealth Games Gold medal in 2002. His impressive career also includes 10 national titles.

Since Nicolas’ retirement in 2004, he has continued to develop high level judo athletes in Canada. He was the head coach of Judo Canada’s world championship team in 2005 and then became the National Head Coach in 2009. His coaching successes include coaching the Bronze medallist from the 2012 London Olympic Games. »

For more history :

1992 Olympic

Ewan Beaton

Michelle Buckingham

Jean-Pierre Cantin

Nicolas Gill

Sandra Greaves

Roman Hatashita

Brigitte Lastrade

Pascale Mainville

Jane Patterson

Lyne Poirier

Patrick Roberge

Alison Webb

Coach : Lionel Langlais

Coach : Andrzej Sądej

1993

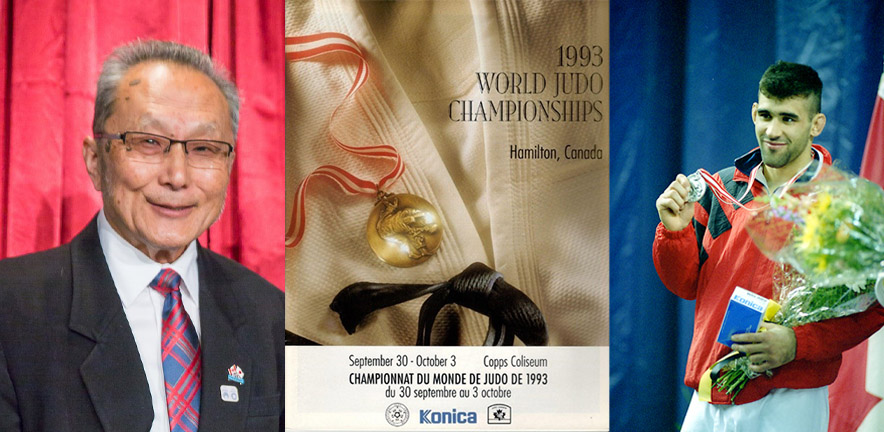

Under the leadership of Jim Kojima, Hamilton, hosts the senior world championships for the first time in Canada highlighted by Nicolas Gill wins his first of three Worlds Championships medals.

Excerpt from the BC Sports Hall of Fame :

« He actively competed in judo in the 1950s and 1960s, first earning his black belt in 1957 and by 2018 one of the rare few in Canada promoted to eighth degree (Hachidan) black belt. He and other Vancouver area judo athletes had to work hard to catch up to the stronger judo clubs in the BC Interior like Vernon, Kelowna, and Kamloops, which formed right after the war and had a head start in terms of development.

“Us young guys we’d go by CPR train to Kamloops or bus to Kelowna to compete with them,” he remembered. “They set the standards for us. We wanted to beat them all the time. It didn’t take us that long, maybe four years. I think it was also the numbers that we had [in the Lower Mainland], which surfaced a more elite group of athletes.”

Soon Jim became involved in other areas of judo and it was here that he truly distinguished himself.

In 1957, he first became involved with Judo BC as secretary-treasurer and has served on many provincial committees right up to the present day. That same year he also became heavily involved with Judo Canada and for the next 66 years served key roles on the referee committee, selection committee, and technical committee among many others. He served as Judo Canada’s vice-president for twenty years from 1968-88 and then as the organization’s president from 1988-94.

The highlight of Jim’s term as president was undoubtedly when Canada hosted the 1993 World Judo Championships at Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum, the most prestigious judo event ever hosted in this country. The last time North America had hosted the worlds was back in 1967 in Salt Lake City, but Jim had built up enough support in Japan that key figures backed holding the championships in Canada. Jim convinced Konica to come on board as a sponsor and the event ended up turning a $40,000 profit. It helped that Montreal’s Nicolas Gill, coming off a bronze medal the year before at the Barcelona Olympics, moved up one podium place to world championship silver in the 86kg weight class in 1993.

“It ended up being a successful championship,” said Jim. “It was a well-run tournament and so we were very happy with the end result. It was a really good experience and a learning experience for Canadian judo in Canada.” »

For more history :

Jim Kojima

World Championships – Hamilton 1993

Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum

Nicolas Gill

David Douillet

1994

Andrée Ruest became the first women President of provincial association in Canada (Quebec)

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

« After that brief first encounter, Andree began to practice with great diligence. By 1973, she won the Provincial Junior Championship as a yellow belt in the 52 kg class, and she repeated in 1974. Andree was a natural competitor. She seemed destined for the national team. Then fate intervened. A car accident in 1976 damaged her knee and put an end to her promising competitive career. What to do now?

Rather than abandon the sport she loved, Andree began to teach as an assistant to Gilles Deschamps. Sept-Îles, 700 miles north-east of Montreal, has one of the largest and most successful dojos in Canada. As a blue belt, Andree was an assistant instructor seven times a week. By 1977 she was promoted to black belt and given her own class to teach.

Judo administration positions in Canada are predominantly held by males so being a female was not exactly the type of thing to assist one’s career at the boardroom level. But Andree had an extra energy that needed an outlet, and by then young age of 17 she was secretary of the North Shore regional executive in Quebec. Surely, one of the youngest executives ever. She held this position for 10 years. In 1994 Andree was elected president of Judo Quebec and as the top executive officer in the province she automatically represented the Quebec region on the Executive Committee of Judo Canada. She is the first female to hold either position. But it is not without sacrifice. Andree spends nearly two hours a day making sure Judo Quebec stays near the top. Additionally, she must travel weekends to various meetings in Montreal, and as part of her duties as a Judo Canada executive member, to other parts of the country as well.

Andree credits her acceptance in Quebec to a more democratic approach. There, it is agreed that for meetings, judo rank will be put aside so that speech may be freer. One may disagree with a 6th Dan, if necessary. This is a more democratic approach to proceedings and has contributed greatly to Quebec’s success in judo. It has certainly worked for Andree. For example, in 1997, the first annual “ Rendez-vous Canada ”, a true international competition, was hosted in Montreal. The same year, Andrée Ruest was chosen as Volunteer of the Years by Sport Québec. »

For more history :

Andrée Ruest

Yudansha Journal May 1997

Yudansha Journal May 1997

(Continue)

Judo Québec

Sept-Îles Judo Academy

Gilles Deschamps

Sept-Îles

Rendez-vous du Canada

Results from 1999 to 2009

Yudansha Journal

December 1998

Sport Québec

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

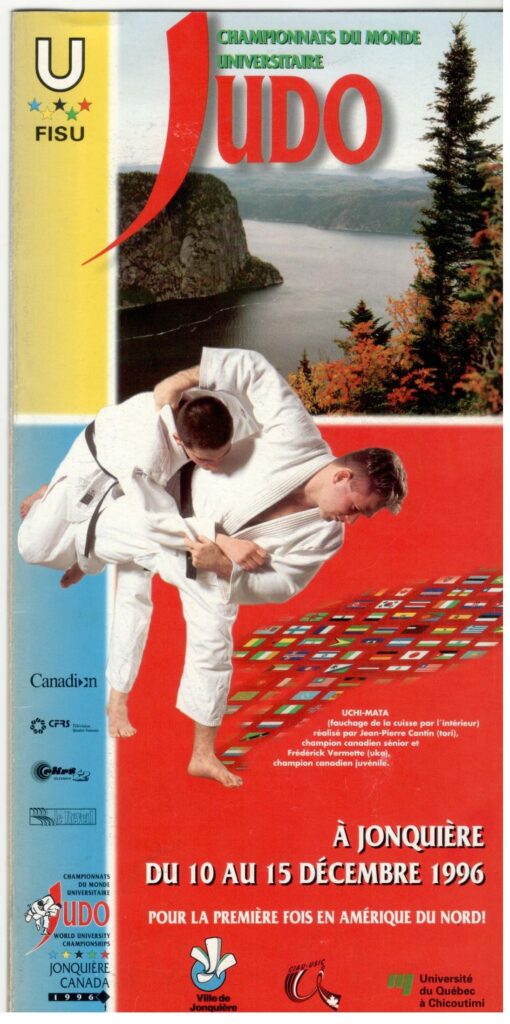

1996 - 1998

1996 Canada is hosting the World University Championships in Jonquiere, Quebec. Nicolas Gill wins a gold medal.

1998 For the first time the Senior National Championships feature a Kata event.

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

« In 1996, under the leadership of Roger Tremblay and coordinated by Patrick Esparbès (who became Chief Executive Officer of Judo Québec [2000-2012] and Chief Operating Officer of Judo Canada [2016-present]), the city of Jonquière hosted the prestigious University World Championships, a major international judo event at the time, as shown by the participation of several future world champions: Cho In-Chul (KOR), Frédéric Demonfaucon (FRA), Isabel Fernandez (ESP), Severine Vandenhende (FRA), Emanuela Pierantozzi (ITA) and Céline Lebrun (FRA). Canada won two medals, a silver by Sophie Roberge (-61kg) and a gold by Nicolas Gill, who had just moved up in -95kg and after his disappointing 7th place at the Atlanta Olympic. »

« It would be impossible to ignore the development of kata and veteran (30 years and older) tournaments, in which Canada played a major role.

1998 was a significant year: for the first time in history, the Senior National Championships had a kata event. For the first time in Legardeur (QC), only the nage-no-kata was offered. The first national champions were none other than Phil Takahashi and James Kendrick, from Ottawa. Six years later, in 2004, the goshin jutsu event was added to the program. Finally, in 2008, IJF recognized katas were added. »

For more history :

Roger Tremblay

Patrick Esparbès

Jonquière

Championnats du monde universitaires à Jonquière

Cho In-Chul (Kor)

Frédéric Demonfaucon (Fra)

Isabel Fernandez (Esp)

Severine Vandenhende (Fra)

Emanuela Pierantozzi (Ita)

Céline Lebrun (Fra)

Sophie Roberge (-61kg)

Nicolas Gill

Jeux d’Atlanta

Senior National Championships

Legardeur

Nage-no-kata

Phil Takahashi

James Kendrick

Goshin Jutsu

The majority of katas

Competitive Kata

Kata Judging

Governance

IJF kata

Daniel De Angelis

Donald Ferland IJF

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

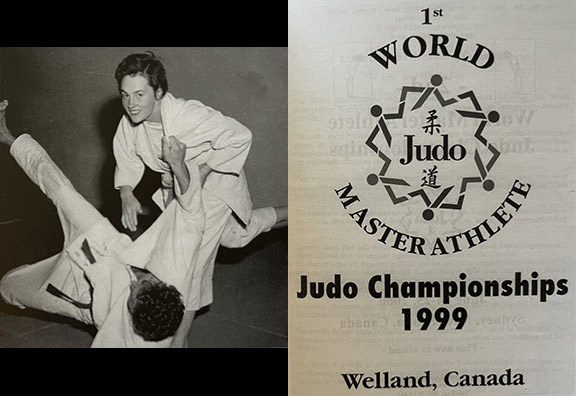

1999

Canada is hosting the first edition of the World Master athlete Judo Championships. The Canadian creation was managed by Liz Roach from Ontario and travelled around the world for 12 years.

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

« 1998 was also the year when the first International Masters Winter Games were held, in Ottawa. Elizabeth (Liz) Roach (1934-2018) was a part of the 4-member team who decided judo should have its own tournament, and that’s how the World Masters Judo Championships were born. The WMJC then travelled around the world for 12 years, writing another page in judo history, touching numerous lives, creating good memories and lifelong friendships. They were where “Judo for life” took all its meaning. Individual, team and kata events were part of the program.

The Canadian creation was managed by Liz Roach and travelled the world between 1999 and 2012: 12 events in 8 countries. 1999 (Welland, ON), 2000 (Sydney, NS), 2005 (Mississauga, ON) and 2010 (Montreal, QC) editions were held in Canada. It’s worth noting that the 2003 edition was held in the mythical Kodokan, in Japan, and the 2008 edition in Brussels had a record number of participants: 1269. The WMJC became the organization recognized by the international judo community as the official authority who could grant the Kata and Veteran World Champion titles.

The IJF, under Marius Vizer, elected in 2007, quickly understood the potential of katas and veterans. In 2009, in Sindenfilgen, in Germany, was organized the first World Veteran Championship sanctioned by the IJF. The following year, in 2010, the second edition was held in Budapest, and kata events were added to the program. Slowly but surely, the IJF attracted the participants of the WMJC, and after a request from Marius Vizer, Liz Roach decided to close down the WMJC.

When Liz Roach died, Mr. Vizer and the IJF publicly recognized her contribution: “The judo family is united in mourning the passing of Liz Roach who was one of the most important figures in the formation of the World Masters Judo Championships, which was the precursor to the IJF’s annual World Veteran Championships.”

For more history :

Liz Roach

Ryudokan Judo Club

Yudansha Journal May 1998

Yudansha Journal September 1999

World Master Judo Federation

Welland, ON

Sydney, NS

Mississauga, ON

Montreal, QC

Kodokan

Kata and Veteran World Champion titles

The IJF

Marius Vizer

Sindenfilgen, in Germany

Concernant les cookies:

Alles akzeptieren: Allow

Einstellungen : Settings

Ablehen : Deny

Budapest

Las Vegas World Championships veterans 2024

Calendar

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

2000

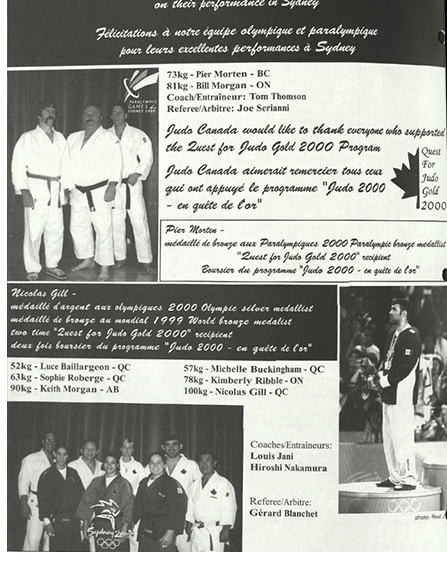

Nicolas Gill wins a silver medal at the Olympics and Pier Morten wins a bronze medal at the Paralympic Games in Sydney, Australia

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

Nicolas Gill:

« Since 1996 Nicolas has moved up to the 95 kg division and has adjusted his schedule of practice and competition somewhat. He is now a second-year student at University of Montreal after being part-time for four and one-half years at CEGEP. In the fall of 1996 and again in 1997, he had arthroscopic surgery on his knee to repair damage, and this kept him on the sidelines during the 1997 World Championship in Paris.

What is the future for Gill? Nakamura-sensei states that Nicolas is one of the best that he has ever coached, and the possibilities of his winning gold in the next Olympics are good – especially as he will have reached his peak of physical maturity and match experience by then.

His sensei was right. In 2000, at the Sydney Olympics, Gill won silver. His second Olympic medal, after the bronze in Barcelona in 1992, truly set him apart as an exceptional athlete. For Gill, Sydney was not his peak, but also the steppingstone for his out of ordinary career. In the following years, he won gold and silver medals at the Commonwealth Francophone Games and the Pan-Am Games. »

Pier Morten:

« In 2000, Pier Morten was the Canadian flag bearer during the Sydney Paralympic Games closing ceremony happening on a Sunday night in the Australian stadium. A member of the judo team, Morten had won a bronze medal that week. It was his seventh time representing his country during Paralympic Games.

The Burnaby-native, in British Columbia, has been a national team member since 1976. 15-time national champion in blind wrestling, Games in Athens. The sport is now widely practiced by male and female athletes in more than 40 countries. Canada has won four bronze medals at the Paralympic Games, including three by Pier Morten. »

For more history :

Nicolas Gill

Sydney, Australia

Sydney Olympics

The 2000 Olympic team

Luce Baillargeon

Michelle Buckingham

Nicolas Gill

Keith Morgan

Kimberly Ribble

Sophie Roberge

Coach : Hiroshi Nakamura

Coach : Louis Jani

Referee : Gérard Blanchet

Pier Morten

Pier Morten vs Scott Moore

Scott Moore

2000 Paralympic team

William Morgan

Pier Morten

Coach : Tom Thompson

Sydney paralympic games

Referee : Joe Serianni

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

2008

Marie-Hélène Chisholm became the first women to hold the position full-time of the assistant national coach for the women’s team

From the Judo Canada web site:

National Team member for nearly 14 years, Marie-Hélène was a very successful competitor. She placed 5th at the Athens Olympic Games, which was the best female result in the history of Canadian judo at the time. The following year she also placed 5th at the 2005 World Championships in Egypt. Marie-Hélène is a certified NCCP level 5 judo instructor. After retiring from competing, she worked at Judo Québec as a provincial coach from 2008 to 2009. She joined Judo Canada in 2009 as the Assistant Coach of the women’s national team. Marie-Hélène kept that position until 2013 and then pursued other opportunities as Judo Canada High Performance Manager. She is also the founder and the chair of the Judo Canada Gender Equity Committee.

For more history :

Marie-Hélène Chisholm

Gala femmes d’influence

Port-Cartier

Athens Olympic Games 2004

Amy Cotton

Marie-Hélène Chisholm

Nicolas Gill

Carolyne Lepage

Keith Morgan

Catherine Roberge

Coach : Hirochi Nakamura

Coach : Ewan Beaton

Coach : Ewan Beaton

2005 World Championships in Egypt

NCCP level 5 judo instructor

Judo Canada High Performance Manager

Founder and the chair of the Judo Canada Gender Equity Committee

Coach of the women’s national team

2012

Antoine Valois-Fortier wins a bronze medal at the London Olympics

Excerpt from the book Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019:

« Antoine Valois-Fortier first started judo when he was 4 years old. By putting their son into a sport where discipline and respect are the main values, his parents were hoping to find a way for him to burn his boundless energy. The trial was a success, and a true passion was born. With his talent and athletic abilities, the Beauport-native rapidly drew attention from the nation team leaders. The results came quickly for the judoka – he won his first World Cup medal in 2010. Despite being successful on the international scene, it was not until the London Olympics that Antoine’s exceptional talent was revealed to the world. By winning an Olympic bronze medal in -81 kg in 2012, he deserved a spot next to his mentor, Nicolas Gill, as one of the best judokas in Canadian history. »

For more history :

Antoine Valois-Fortier

Olympic Games London 2012

City of London

Amy Cotton

Alexandre Emond

Sasha Mehmedovic

Joliane Melançon

Sergio Pessoa Jr.

Nicholas Tritton

Antoine Valois-Fortier

Kelita Zupancic

Coach : Nicolas Gill

Coach : Sergio Pessoa Sr.

Beauport Judo Club

Daniel Tabouret

Patrick Roberge

Beauport

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

2013

Jessica Klimkait & Louis Krieber-Gagnon became Cadet World Champions in Miami, USA

Kyle Reyes becomes Canada 1st Junior World Champion in Ljubljana, Slovenia

Excerpts from a Judo Canada articles:

« Montreal, August 10, 2013 – Quebec Judoka Louis Krieber-Gagnon grabbed the title in the Under 81kg class, Saturday, at the Cadet Judo World Championships presented in Miami, Florida.

“I’m really happy. This is really hard feeling to explain; I dreamed of winning this title but I didn’t actually expect to become World Champion. I think I performed pretty well today; I also did train very hard to do well at this competition,” explained the Quebecois athlete.

“This was an outstanding day for Louis! His semi-final and final matches were real battles and he needed to dig deep to pull out these wins. Louis was 5th two years ago at the World Championships and he returned to on a mission to improve his standing from the last time,” said Coach Ewan Beaton.

Krieber-Gagnon started the day with successive wins – all by Ippon – against Estonian German Duran and Tunisian Oussama Mahmoud Snoussi. In the quarter finals, the Canadian won against Israel’s Idan Vardi who was disqualified.

The Quebec native then met Russia’s Mikhail Igolnikov in the semi-finals, where both judokas scored Waza-aris; Krieber-Gagnon then took the lead with a Yuko and went on to victory.

“That was an impressive win because the Russian has not lost an international match in the past three years and was seen as the clear favorite to win,” explained Beaton.

In the final round, Krieber-Gagnon defeated the Netherlands’ Frank De Wit by Waza-ari to win Canada’s second World Championship of the weekend. Ontario’s Jessica Klimkait took the title in the Under 52kg category Friday in Miami. »

« Montréal, October 26th, 2013 – The judoka Kyle Reyes became the first Canadian ever to win a Junior World Championship title, Saturday, after claiming gold in the under 100 kg class in Ljubljana, Slovenia. No Canadian men’s judoka had won a medal since 1992, when Nicolas Gill came away with a silver medal in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Reyes began his day with successive victories over the Kyrgyzstani Bolot Toktogonov, the German Marius Piepke and the Japanese Ryuko Ogawa with ippons. In the semifinal he defeated the Belgian Toma Nikiforov with a waza-ari, before going on to claim the gold medal with an ippon over the South Korean Leehyun Kim at the 2m 42s mark.

“It was really incredible to have so much support from my teammates today! I knew that Canada had never had a junior world champion, but I never thought I would be the first,” exclaimed Reyes, who has been living in Japan for a number of years. “It was my first and last Junior World Championships and I was pretty nervous, but I managed to put all that aside to have a great day.” »

For more history :

Jessica Klimkait

Louis Krieber-Gagnon

Cadet World Champions 2013

The Canadian Team

Miami, United States

Kyle Reyes

Junior World Championship

Ljubljana, Slovenia

Judoka, The History of Judo in Canada, 2019

2014 - 2016

2014 Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard wins a bronze medal at the Junior World Championships she is the only Canadian to win two medals at this event

2014 Shortly after Judo Canada open their world class NTC at the INS-Q, Antoine Valois-Fortier wins his first world medal. He currently stand with an Olympic bronze and 3 worlds medal

2016 The National office move to Montreal to be closer to the national training centre

Excerpt from the Judo Canada website :

« Montréal, October 23, 2014 – The Quebecoise judoka Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard will leave the Junior World Championships in Miami with a bronze medal around her neck. She’s the only Canadian to have won a medal on Thursday.

Fighting in the under 57 kg class, the athlete from Longueuil lost in the semi-final against the Japanese Momo Tamaoki. She fought back in the bronze medal bout and won against the Netherlander Dewy Karthaus.

Earlier, she had won her first bout against the Pole Anna Borowska, followed by another victory against Nilufar Muhiddinova, from Turkmenistan. At the end of the preliminary round, the Quebecoise judoka also took down the Israeli Timma Nelson Levy.

“Catherine’s goal was to confirm the podium she had reached last year. She ends her junior years with a second international medal. She had a good day. We’re proud of her” said Jérémy LeBris, one of the coaches at the championships.

“She continues her journey towards the Olympic Games next week, at the Abou Dabi Grand Prix. Her next big goal is to win a medal during the next Senior World Championships, in August 2015” he added. »

Excerpt from the judoinside.com :

« Canadian judo coach Antoine Valois-Fortier won the Olympic Games bronze in London 2012, in Rio he finished seventh. Valois-Fortier fought in the 2014 World Championships final vs Tchrikishvili and took bronze in 2015 and 2019 in the Budokan in Tokyo. He won 25 World Cup medals. In 2017 he won gold at the Grand Prix in Hohhot. Antoine took bronze at the Grand Prix in Tbilisi and Antalya in 2019. He took silver at the Grand Prix in Montreal and Zagreb and retired in December 2021 becoming national coach of Canada to embark on a new Olympic cycle leading to Paris.»

For more history :

Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard

Judo Junior World Championships 2014

United States of America, FT. Lauderdale

NTC at the INS-Q

NTC at the INS-Q

Notre-Dame-de-Grâce

Antoine Valois-Fortier

Judo World Championships 2014

2018 - 2019 - 2020

2018 Priscilla Gagné writes history by being the first women to win a medal (bronze) at the Paralympic World Championships in Odivelas, Portugal & Keagan Young wins a bronze medal at the Youth Olympic Games in Buenos Aires.

2019 Christa Deguchi becomes the first ever Canadian senior world champion.

2020 At the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games, Jessica Klimkait becomes Canada’s first female Olympic medallist in judo, followed the next day by Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard, each winning a bronze medal. A few days later, at the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games, Priscilla Gagné won a silver medal, becoming the first Canadian woman to win a Paralympic medal in judo.

Excerpts from the Canadian Paralympic Committee website:

«ODIVELAS, Portugal – Montreal’s Priscilla Gagné won the bronze medal Friday in women’s 52 kilos at the Para Judo World Championship for visually impaired.

The 32-year-old Paralympian ended her journey by winning by waza-ari against Uzbek Sevinch Salaeva. Ukrainian Inna Cherniak was crowned world champion against German Ramona Brussig and South Korean Song Nayeong stood next to Gagné on the podium’s third step.

Earlier in the day, Gagné won both her fights in repechage by ippon, first against Turk Semra Akgul then against Russian Alesia Stepaniuk. She had one victory and one loss in the preliminary rounds.

Gagné, who has a condition called retinitis pigmentosa, earned her first major title a few weeks ago when she won the women’s 52 kilos title at the Pan Am Para judo championships in Calgary.»

Excerpts from Team Canada website:

«Young’s bronze medal is not only Canada’s first of Buenos Aires 2018, but it marks Judo Canada’s first in Youth Olympic Games history. He won his medal against Alex Barto of Slovakia.

Young didn’t take the easy path to his Youth Olympic medal, the Canadian lost his quarter-final match against Algerian Ahmed Rebahi, sending him into the repechage round.

In repechage, he won his first match versus Moroccan Anwar Zrhari. Next up he faced Venezuelan Carlos Paez. He defeated Paez, leading him to the bronze medal match. »

Excerpts from Sportcom website:

«Montreal, August 27, 2019 – The third day of the World Judo Championships held in Tokyo, in Japan, was like a fairy tale for Canadian judoka Christa Deguchi, crowned world champion in -57 kg.

On top of earning the prestigious title for the first time in her career, Deguchi did it in her native country. Deguchi grew up in Nagano, less than 300 kilometres away from the Japanese capital. It was also a first gold medal in Senior World Championships in Canadian history, making the athlete even prouder.

“I can’t believe I won! I was surprised and happy, and then extremely proud to win Canada’s first gold medal,” said Deguchi, who’s been representing Canada since 2017 and whose father is from Winnipeg. “I wasn’t sure I’d be powerful enough to win Worlds, but I think I’ve proven I have everything it takes to be on top,” she added, exhausted from her performance.

A scenario worthy of a Hollywood movie happened in the finale, when the Canadian faced Japanese Tsukasa Yoshida, number 1 on the world ranking and defending champion, who had eliminated Deguchi in the semifinal in 2018. “I took my revenge! We are the same age and we grew up together. I’ve known her since I was 15, so I know her very well.” »

Excerpts from Team Canada website:

« In her Olympic debut at Tokyo 2020, Klimkait lost her semifinal in Golden Score time, but rebounded to win her bronze medal match against Kaja Kajzer of Slovenia. That made her the first Canadian woman to ever win an Olympic medal in judo. When Catherine Beauchemin-Pinard won her own bronze in the 63kg event, that marked the first time Canada had ever won multiple judo medals at one Olympic Games. »